The Letters of Eileen Chang

One of my personal assignments in this Hong Kong apartment is to go through the file cabinets and sort through all the letters and documents. And there are plenty of them. Of the letters, the most important ones would be those between my parents and the late Chinese writer Eileen Chang.

Eileen Chang has the standing of being the greatest contemporary writer and at the center of a cultural industry about her. She is bigger in China than Sylvia Plath in the United States. There are books of photographs of all the buildings that she reputedly lived in; there are biographies about her and all the people in her life; there are books of photographs of all the places in Shanghai that she should have visited when she lived there; there are books about all the illustrations that accompanied the newspaper short essays that she wrote; there are doctoral dissertations about post-feminism in her work; and so on. It is an industry because this kind of stuff somehow sells well because the demand exceeds the supply.

How did she ascend onto the peak of the pantheon? Well, she wouldn't know because she never asked for it and she never did anything to make that happen. So that may be the first secret -- the harder one tries, the more unlikely it is for people to grant that status; conversely, the less one cares or reacts, the more likely people will confer that honor.

The second key is that Eileen Chang was famous for being reclusive. She had only a handful of close friends, and her editor at Crown Press had never even met her in person after decades of collaboration. It has been remarked that the Chinese model hero Lei Feng could afford to be turned into a paragon of moral virtue and courage precisely because his life was so brief, leaving no time or opportunity for him to commit bad deeds that could tarnish that idealized image. Eileen Chang lived long, but she provided very little information about herself to the outside world, which was then allowed to project their own ideas and feelings about her.

Given the burgeoning industry that revolved around the cult of Eileen Chang, any information about her is regarded as valuable. Just a scrap or two might be enough to write yet another book. So who are those few close personal friends who might offer some insights? Upon her death in Los Angeles, she left a will that gave everything to my parents. Shortly after, the will executor sent all her personal possessions in fourteen carton boxes to this apartment here. After the contents were sorted out, much of the stuff such as the manuscripts and letters has been forwarded to Crown Press for organization.

So who are my parents? What did they have to do with her that she left them everything, including her entire literary estate, over her own family in her will? I will quote the relevant parts of my father's essay titled Some Private Words On Eileen Chang included in Crown Press' memorial volume.

In the preface to Eileen Chang's Art Of Literature, Professor C.T. Hsia mentioned that Eileen Chang was closest to me and my wife, and that she was a colleague of my wife. These claims need to be clarified and explained.

When we were in Shanghai, we did not know Eileen Chang although we were her loyal readers. In 1952, Eileen left Shanghai to come to Hong Kong. At first, she lived at the YWCA and counted on translation to earn a living. Based upon what I know, she translated the works of Ernest Hemingway, Margery Lawrence, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Washington Irving for the United States Information Services. At that time, my wife was also translating for the same organization during her spare time. So this was how it came about that people thought that they worked at the same place.

Eileen was not really interested in translation. She said: "I forced myself to translate Emerson. I had no choice. It would be the same as if I were translating a book about dentistry." Another time, she complained: "Translating the novel by Washington Irving was like being forced to speak to someone that you don't like. You can't help it, and you can't run away either."

Eileen was staying in a single room at the YWCA. But as her translation work became known, people began to look her up. This is what she detested most, so she asked us to rent a room on a side street near us. The room was sparsely furnished, and it did not even have a writer's desk . So she had to write on the small stand next to her bed. She has always believed that possessions are a burden that interfered with personal freedom. She would borrow books to read instead of buying them, "because as soon as one buy the books, it is like as if one has grown roots."

We would visit her and chat with her in order to relieve the loneliness and pain when her writing was not coming along well. During this period, she was writing the commissioned novel Naked Earth based upon a synopsis provided by someone else, so she was not having a good time at all about writing according to specification, and she would never do that again in her life. Sometimes, when I was busy, my wife would go visit by herself. They liked each other, and they can talk forever whenever they met. But no matter how well things were going, Eileen would send my wife home after seven o'clock. Later on, Eileen would give my wife the title of "My eight o'clock Cinderella" who had to return home to her own family by that designated hour. This was the period during which Eileen was closest to us.

In 1955, Eileen took the President Cleveland ocean liner to leave Hong Kong for the United States. The two of us were the only ones to see her off at the pier. When she reached Japan, she sent a six-page letter, which included: "After we said goodbye, I cried all the way back to my room. This departure was completely different from the happiness that I felt when I left Hong Kong last time. As I write these words, my eyes are welling with tears again." Then she wrote that she wanted to write down everything about this trip, because "there are many small things that I would not write about later, so I ought to write them when I have the time now."

This was her principle later on. She would tell us about all things big and small, "continuing on and on, which probably would not be told in live conversation." She would write whenever she can, sometimes long and other times short, and her tone would change with her environment and mood.

Eileen thought that the world changes so much that nothing can be relied upon. That was why she only trusted a few people, and she told us repeatedly: "Write when you have the time ... but I won't be upset if you don't write for six months or a year. As long as you remember me, you remember me." This introverted and asocial woman would have a deep and long-lasting friendship with us. It has been more than twenty years by now, and we have a huge pile of her letters. Occasionally, we would bring out those letters to read, and it was like as if we were chatting in that small room again.

At this point, it should be clear that the trove of letters may be the foundation of a brand new cultural empire of textual exegeses. Most of those letters have been forwarded to Crown Press, so there is no point in contacting me to get the inside edge. Within this apartment, I have come across a few more letters that had been misfiled by my parents previously. As I read them, I have this taxonomy:

First, the letters contain a lot of financial details about loyalty payments, contracts, movie rights and so on. Eileen Chang was shielded from these necessary evils by her own choice, and my father acted as her literary and business agent and provided her with the summaries. Also, Mr. Ping at Crown Press was a trustworthy old friend of many decades who did much more than a publisher is obliged to. It suffices to say that Eileen Chang did not suffer from want or need, and those kinds of detail do not illuminate on her literary accomplishments.

Second, the letters contain some personal information which should be nobody's business either. For example, why should anyone care that an author had a temporary case of incontinence in 1978 or some such?

Third, Eileen Chang was good enough friends with my parents that she held nothing back. The letters contain some very frank but unkind comments about her relatives, associates and other friends, including some living persons for whom it would be extremely painful to read. I, for one, cannot say that these comments ought to be published at this time for the sake of literature. Even more, I will say that I would never have put those kinds of sentiments into any form of writing about anyone.

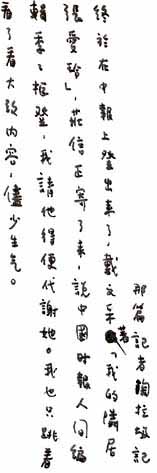

Fourth, there is probably some information that would be quite interesting from a literary point of view. I am going to use just one quirky example from a letter signed and dated December 27 that I found yesterday. The signature and date are shown below in a scanned image (and this may be the first time that her sign-off has ever been shown to the public). This shows one technical problem with the letters, as she only put down the day and month and not the year, so that it is not a simple project even to try to date the letters in chronological order.

![]()

Here is the short excerpt from this three-page letter:

Translation: "That article based upon the reporter going through my garbage has finally been published in Center Daily News: Dai Wencai's 'My neighbor Eileen Chang.' Chuang Xinchong mailed it to me and wrote that China Times' supplement editor Lai Cuiqi refused to publish it. I have asked Chuang to thank Lai for me. I only glanced at the article. I got the general idea, and I tried not to get too upset."

This was a cause célèbre in its own time when this reporter from Taiwan went to Los Angeles, found a place near Chang's apartment, followed her around secretly and ploughed through her garbage in order to write this article about the reclusive author. So now at least we know how the subject felt about her stalker. While this was not earth-shattering news, it does at least answer one question.