The Art of Abu Ghraib

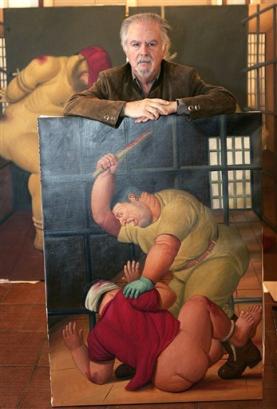

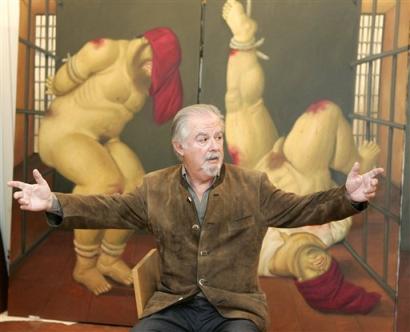

All photo credits: AP Photo/Francois Mori

Photo: Revista

Diners

(The Independent) The Art of Abu Ghraib. By Elizabeth Nash. April 13, 2005.

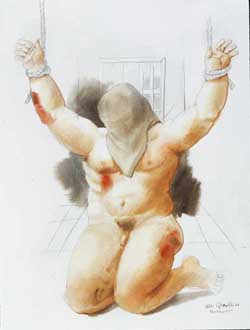

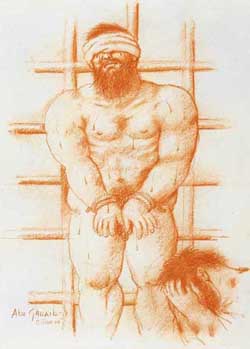

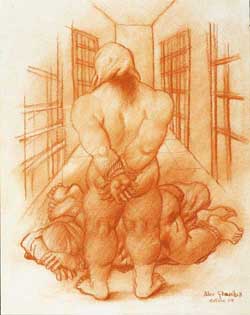

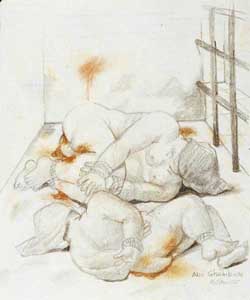

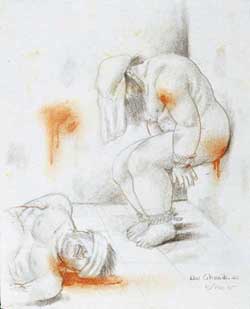

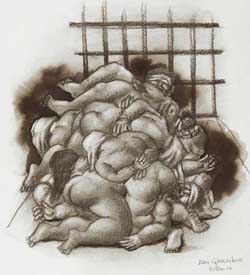

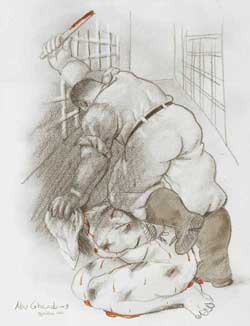

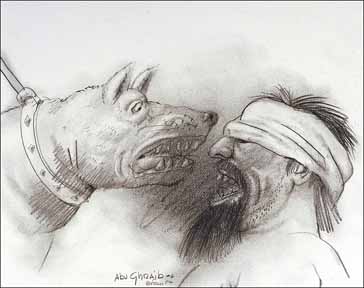

The horrors of Iraq's notorious Abu Ghraib prison have been brought to shocking life by the brush of Colombia's best-known painter, Fernando Botero. His series of new works will go on show in Europe in June.

The artist, who is known worldwide for his paintings of voluptuous females and prosperous businessmen, says that anger drove him to portray the tortures inflicted by American soldiers upon Iraqi detainees in an Iraqi prison. "This conduct by the Americans was a total shock for me," Botero told the Colombian magazine Diners in an interview. "I am increasingly sensitive to injustice, which makes my blood boil, and these paintings were born from the anger provoked by this horror."

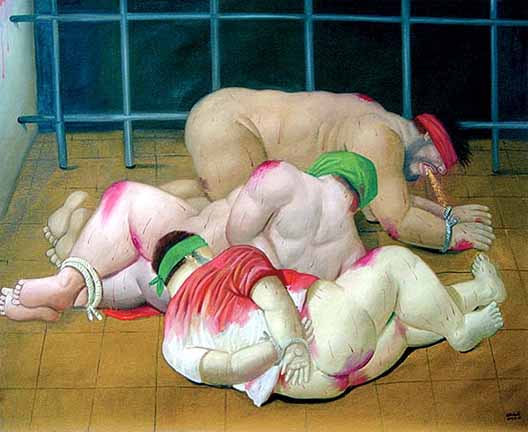

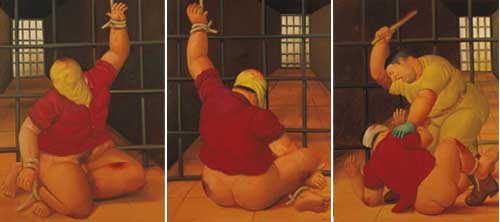

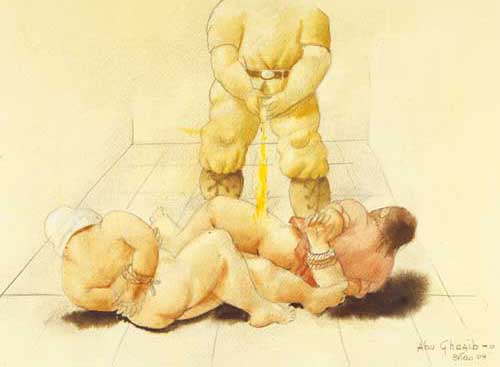

The works, which are to be exhibited in Italy and then Germany, include two enormous triptychs showing life-sized images inspired by the photographs that horrified the world. They show men blindfolded and dressed in women's underwear; men and women being beaten or harried by dogs, and bleeding bodies forced into humiliating postures. One painting shows three naked, bound and hooded Iraqis stacked in a human pyramid, with blood pouring from their wounds. Many figures have the roly-poly chubbiness characteristic of Botero's work, while others look more like body-builders.

"As I'm an avid reader, I started to read everything I could about what happened, and I was shocked because Americans are supposed to be the model of compassion... The things that happened in the Iraqi cells were serious, very serious. And especially because they flouted completely the conditions imposed by the Geneva convention concerning the treatment of prisoners of war," Botero said. He added that the written descriptions of the abuses inspired him more than photographs.

...He wants the series to be shown in the US, since "the matter concerns that country above all." The paintings will not be sold, but will remain part of his personal collection and loaned to museums which frequently invite him to exhibit, the artist said. "I had no commercial intention in painting these works. I produced them purely to say something about the horror. And since all art is communication, it's more important that they are seen in museums and big public exhibitions than that they are hidden away in the house of a private collector." His aim, he said, was to brand the images on the conscience of the world, in the way that Picasso's Guernica preserved forever the memory of how innocent civilians were bombed during the Spanish civil war.

(New York Times) 'Great Crime' at Abu Ghraib Enrages and Inspires an Artist. By Juan Forero. May 7, 2005.

Fernando Botero, Latin America's best-known living artist, shocked the art world last year when he broke sharply from his usual depictions of small town life to reveal new works that depicted Colombia's war in horrific detail.

Now, Mr. Botero, 73, who lives in Paris and New York, has taken on an even more explosive topic: the torture of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib. Forty-eight paintings and sketches - of naked prisoners attacked by dogs, dangling from ropes, beaten by guards, in a mangled heap of bodies - will be exhibited in Rome at the Palazzo Venezia museum on June 16.

"These works are a result of the indignation that the violations in Iraq produced in me and the rest of the world," Mr. Botero said by telephone from his Paris studio.

"I began to do some very fluid drawings, and then I began to paint and the results are 50 works inspired by this great crime."

Mr. Botero said the paintings and sketches, done in oils, pencil and charcoal and part of a 170-piece traveling exhibition, would also be shown at the Würth Museum in Germany in October and at the Pinacoteca in Athens next year before returning to Germany. The exhibition was first made public last month, when Diners, a Colombian magazine, published photographs of the works.

Mr. Botero's work had, until recently, not been known for making political statements. Instead, for 50 years, his paintings had been associated with the placid, pastoral scenes of the small-town Colombia of his childhood, featuring ordinary people, aristocrats, military officers and nuns, all of them extravagantly corpulent.

But last year, his paintings of Colombia's long guerrilla war, full of blood, agony and senseless violence, became a big draw in European galleries, surprising followers astonished by Mr. Botero's bold departure in substance, if not style. Mr. Botero explained that he had decided he could not stay silent over a conflict he called absurd.

Now, he said, his indignation over war and brutality may turn up increasingly in his work.

"I rethought my idea of what to paint and that permitted me to do the war in Colombia, and now there's this," he said. "And if there's something else that compels me in the future, then I will do it."

Mr. Botero, citing the Impressionists and the many works of a favorite of his, Velásquez, said he had once thought that art should be inoffensive, since "it doesn't have the capacity to change anything."

But with time, and his growing outrage, Mr. Botero said he had become more cognizant that art could and should make a statement.

He pointed to the most famous antiwar painting of the 20th century, Picasso's masterpiece that depicted the German bombing of Guernica, Spain. Had Picasso not produced "Guernica," Mr. Botero said, the town would have been another footnote in the Spanish Civil War.

He said he read about Abu Ghraib in The New Yorker, then followed European news accounts. Calling himself an admirer of the United States - one of his sons lives in Miami - Mr. Botero said he became incensed because he expected better of the American government.

His new paintings and sketches - conceived not from photographs or specific acts of torture but rather from his reading of news reports - depict gruesome scenes of prison abuse. One inmate hangs from the ceiling, a rope around his ankle. Another work shows a soldier beating a prisoner with a baton, while yet another portrays a soldier urinating on an inmate. In many of the works, inmates simply scream in pain.

Mr. Botero said the works being exhibited, and those he has continued to create on Abu Ghraib, were not for sale because it would not be proper to profit from such events.

In Europe, where sentiment against the Iraq war is strong and Mr. Botero's work is well received, news of the paintings and sketches has already generated interest. In Germany, museums in Hanover and Baden Baden want to stage exhibitions exclusively of Mr. Botero's works on Abu Ghraib.

No exhibitions in the United States are planned, though Mr. Botero said he would like nothing more.

His previous works are on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and many others.

"If any museum wants to show works of torture, well, I would be delighted," Mr. Botero said. "The museum that decides to show it would have to be conscious that many people would be repulsed and be against it."

¿Por qué decidió pintar esta serie sobre lo sucedido en Abu Ghraib?

—Por la ira que sentí y que sintió el mundo entero por este crimen cometido por el país que se presenta como modelo de compasión, de justicia y de civilización.

¿Después de pintar el horror de la violencia colombiana contemporánea pensó que tenía algún compromiso de reflejar también este acontecimiento de violencia mundial?

—En el arte hay que revaluar siempre las ideas, poner todo en tela de juicio. Yo siempre creí y prediqué que el gran arte se hizo siempre sobre temas más bien amables, con muy pocas excepciones. Y es cierto. Por ejemplo, existen millares de obras hechas por los impresionistas, y aún no he visto una que represente un tema dramático. Sin embargo, situaciones tan hirientes como la violencia en Colombia y ahora la tortura en la prisión de Abu Ghraib lo hacen a uno pensar diferente.¿En el momento de la gestación o creación de estas nuevas obras sintió que existía alguna similitud entre estos dos hechos de horror?

—No. La situación es distinta. La violencia en Colombia casi siempre es producto de la ignorancia, la falta de educación y la injusticia social. Lo de Abu Ghraib es un crimen cometido por la más grande Armada del mundo olvidando la Convención de Ginebra sobre el trato a los prisioneros.¿Espera que esta serie, que seguramente será polémica, tenga efecto político en el mundo?

—No. El arte nunca tuvo ese poder. El artista deja un testimonio que adquiere importancia a lo largo del tiempo si la obra es artísticamente válida.¿Cómo cree que la comunidad internacional, especialmente la norteamericana, va a recibir esta obra suya tan dramática sobre un hecho real y actual?

—Son obras nacidas de la ira ante tal horror. El cómo sean recibidas no fue una consideración en el momento en que las hacía.¿Llama la atención la cantidad de obras que pintó sobre el tema. ¿Cómo fue el proceso de investigación y creación?

—Soy adicto a las noticias, a los periódicos y a las revistas. Además, a diario miro la internet y vivo informado. Han sido muchas las crónicas escritas sobre el tema, especialmente el magistral artículo aparecido en The New Yorker, el cual reveló la situación que se vivía en las cárceles controladas por los norteamericanos. A medida que me iba enterando sentía más la necesidad de decir algo sobre tal horror. El año pasado empecé a dibujar y a pintar, y son ya casi cincuenta obras las que he hecho sobre el tema.¿Por cuál de esos dos géneros de obra que usted hace, cree que irá a ser más recordado en la historia del arte colombiano y universal?

—El tiempo y la historia son grandes palabras con las que no me quiero meter.¿Es posible que en el futuro vuelva usted a pintar una serie específica sobre algún tema de la actualidad política?

—Es muy posible. Cada vez me siento más sensible a la injusticia que me hace hervir la sangre.¿Aparte de la exposición en Roma en junio próximo, ¿qué destinación tendrán estos cuadros?

—Estas obras serán exhibidas próximamente en dos museos, en junio en Roma y en octubre en Alemania. No tengo la menor intención de venderlas. Las mostraré donde me inviten a exponer, ojalá en los Estados Unidos. No hay que olvidar que la gran mayoría de los norteamericanos condena la práctica de la tortura. La prensa de ese país ha denunciado permanentemente los hechos ocurridos en Abu Ghraib.