Illustration:

ill. 2.9 (set: 2.8)

Author:

Tan Dun (1957-) 谭盾

Date:

1996

Genre:

sheet music

Material:

scan, paper, black-and-white; original source: music sheet, paper

Source:

Tan Dun 1996: Tan, Dun. Orchestral Theatre III: Red Forecast. New York: G. Schirmer Inc., 1996:105.

Courtesy:

Schirmer

Keywords:

Red Forecast, Tan Dun, Zaofan you li, To rebel is justified, Internationale, sun

Tan Dun: Red Forecast

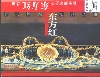

Is it irony that speaks from these juxtapositions, these denaturations, these curtailments, these overwritings? Perhaps yes, but this interpretation again does not explain why a huge Mao portrait toward the end floods the video screen with red, as sun rays burst from the screen like shooting stars. This picture of triumph and glory is accompanied by extremely augmented shreds from “Sailing the Seas,” jazzy elements derived from the “Internationale,” and, in trumpet flourishes, bits and pieces from “Red Is the East” as can be seen in ill. 2.9 (p. 105, at around min. 39:50 in mus. 2.9). The bric-à-brac of melody fragments is accompanied by a contagious monotonous rhythm that gradually takes over the entire orchestra, eventually becoming a huge din of wild and improvised noises, until everything breaks off suddenly and unexpectedly to end in a short silence (p. 107H) followed by rhythmically determined afterthoughts (p. 108). Is this a depiction of the famous chaos (乱 luan) that the Chairman—whose favorite maxim was “to rebel is justified” (造反有理 zaofan you li )—so loved? Or is this a critical attack on the vandalism that resulted when this idea became the core of Party policy?

If the latter interpretation is correct, then why does the next and last movement, programmatically entitled “Sun,” begin with a heart-rending oboe melody (woodwind!) and talk, apparently quite seriously, of the sun’s promise of brightness? “Sunshine, exposing sunshine, yearning. The sky will be brighter than ever” are the words sung by the soprano, if with the instruction to intone them “very sadly.” Why does the sky become redder and redder around the singer and all over the video screens and the stage while she sings: “Air returns, pressure goes, rain waits, in the red sunshine with clouds. Highs, highs, highs near eighty nine—ty nine” when the text is combined with the fate motif from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, intoned, time and again, in the timpani (p. 116–117)? Does the elongation on “eighty nine” before it resolves into “(nine-)ty” as juxtaposed with Beethoven’s fate motif have meaning? Does it indeed allude to the massacre of 1989 as does the triumphant citation of “We Shall Overcome” throughout the piece? Why then does the text say “pressure goes?” And if this is really an allusion to the bloody end of the student demonstrations in 1989, then the reappearance of the happy dance motif—not unlike the seemingly out of place treatment of war imagery in the fourth movement—makes little, if any, sense (p. 118, at around 40:00 in mus. 2.9). Is the juxtaposition of sun, clouds, and possible rain in “rain waits, in the red sunshine with clouds” perhaps a covert criticism of the red sun, Mao himself? It may very well be, especially since this is the second time Tan Dun’s text talks of clouds in connection with the sun?