Media file:

mus. 2.9

Title:

Tan Dun Red Forecast, part 2

Source:

Heidelberg catalogue entry, DACHS Archive

Courtesy:

Schirmer

Keywords:

Tan Dun, Red Forecast, the Internationale, Red is the East, Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman, Cultural Revolution, contemporary China

Tan Dun Red Forecast, part 2

The fifth movement of Tan Dun’s 1996 Red Forecast “Storm and Documentary” of which we can hear an excerpt here, is a surrealist collage made up of different political songs—“We Shall Overcome,” the “Internationale,” ”Red Is the East”—as well as another important song during the Cultural Revolution, “Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman.”

How, then, does one interpret the dizzying combination of the Maoist words “There will be thunderstorms, press east toward west by evening” and pictures of a red sun and Mao Zedong waving his hand up and down in fast motion, together with “We Shall Overcome” played very slowly and emotionally in the high strings in Tan Dun’s piece? And what do we make of the appearance, just a fraction later, of “Navigating the Seas Depends on the Helmsman” (ill. 2.8, p. 84C, b. 43) and small fragments from both “Red Is the East” (ill. 2.8, p. 84C, b. 44/45) and the “Internationale” (Ibid., b. 46–50) in the woodwinds, again accompanied in counterpoint by “We Shall Overcome” in the strings (Ibid., b. 45, mus. 2.9)?

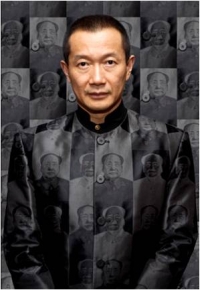

To equate Mao’s revolution to a thunderstorm pressing towards the West may be acceptable (indeed, it is his own words that the “East wind prevails over the West wind” [东风压倒西风] (Mao 1957a). But to show in fast motion the image of the Great Chairman repeating the same characteristic movement again and again like a puppet, and all this to the sounds of “We Shall Overcome,” a political song of American origin, that appears as a dominant counterpoint in the strings while the hymn to the Helmsman is delegated to the unimportant woodwinds and “Red Is the East” and the “Internationale” are fragmented into oblivion (as seen in the score)—this may be considered blasphemy!

Is it irony that speaks from these juxtapositions, these denaturations, these curtailments, these overwritings? Perhaps yes, but this interpretation again does not explain why a huge Mao portrait toward the end floods the video screen with red, as sun rays burst from the screen like shooting stars. This picture of triumph and glory is accompanied by extremely augmented shreds from “Sailing the Seas,” jazzy elements derived from the “Internationale,” and, in trumpet flourishes, bits and pieces from “Red Is the East” as can be seen in ill. 2.9 (p. 105). The bric-à-brac of melody fragments is accompanied by a contagious monotonous rhythm that gradually takes over the entire orchestra, eventually becoming a huge din of wild and improvised noises, until everything breaks off suddenly and unexpectedly to end in a short silence (p. 107H) followed by rhythmically determined afterthoughts (p. 108). Is this a depiction of the famous chaos (乱 luan) that the Chairman—whose favorite maxim was “to rebel is justified” (造反有理 zaofan you li )—so loved? Or is this a critical attack on the vandalism that resulted when this idea became the core of Party policy?

If the latter interpretation is correct, then why does the next and last movement, programmatically entitled “Sun,” begin with a heart-rending oboe melody (woodwind!) and talk, apparently quite seriously, of the sun’s promise of brightness? “Sunshine, exposing sunshine, yearning. The sky will be brighter than ever” are the words sung by the soprano, if with the instruction to intone them “very sadly.” Why does the sky become redder and redder around the singer and all over the video screens and the stage while she sings: “Air returns, pressure goes, rain waits, in the red sunshine with clouds. Highs, highs, highs near eighty nine—ty nine” when the text is combined with the fate motif from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, intoned, time and again, in the timpani (p. 116–117)? Does the elongation on “eighty nine” before it resolves into “(nine-)ty” as juxtaposed with Beethoven’s fate motif have meaning? Does it indeed allude to the massacre of 1989 as does the triumphant citation of “We Shall Overcome” throughout the piece? Why then does the text say “pressure goes?” And if this is really an allusion to the bloody end of the student demonstrations in 1989, then the reappearance of the happy dance motif—not unlike the seemingly out of place treatment of war imagery in the fourth movement—makes little, if any, sense (p. 118). Is the juxtaposition of sun, clouds, and possible rain in “rain waits, in the red sunshine with clouds” perhaps a covert criticism of the red sun, Mao himself? It may very well be, especially since this is the second time Tan Dun’s text talks of clouds in connection with the sun?