Three Character Classic on Agricultural Techniques

The Three Character Classic on Agricultural Techniques (农业技术三字经 Nongye jishu Sanzijing) illustrates the pragmatic nature of these publications (NYJSSZJ 1964). This book, and the many variations of it published at around the same time, may be seen as a direct answer to criticisms of Confucius and Confucianism put forward then: in these discussions, the fact that Confucius did not teach practical matters about agriculture and even discouraged his students to learn anything about agriculture (Louie 1980, 72) played an important role. These new variations on the Three Character Classic use a Confucian template, then, to create an extremely detailed countertext to this very work and the ideas propagated therein. The text advises readers, for example, as here, how to deal with used up and salt-washed fields, how to apply three-year circles, how best to install irrigation systems, and how to fight plant diseases and pests.

Illustrations also show exactly what corn looks like (ill. 3.8), when fertilizer is applied properly and when it is not, for example, and what are proper hoes and which way they should be held and used with particular plants. We also find exact instructions on how to apply pesticides and on how to treat those who have become ill from exposure to them (NYJSSZJ 1964, 42).

With its focus on all of these details, the text may appear to be, at first sight, quite far from preaching anything that could be called “Confucian morality.” Surprisingly, however, it also contains Confucian ideas: one of the most significant points of the text is its admonition to heed the words of the old and thus to combine old and new knowledge to best effect: “good experiences must be handed on” (学农活问老农好经验要继承) (NYJSSZJ 1964, 2). Reverence for the “old,” which is one of the central points in the original Three Character Classic, is not at all discarded, then, in this newer text. Another idea echoed here is the basic premise of the Great Learning, one of the canonical Four Books, that if one’s family is in order, then the country will be governed well (家齐而后国治).

The quintessential phrase recurring throughout the text of this agricultural Three Character Classic is that the commune members will be wealthy (社员富) and the country will be strong (国家强) if all the things explained throughout the book are done well (e.g., NYJSSZJ 1964, 47, 59). Again, the text thus implicitly follows the logic of the Great Learning in arguing that to keep the family in order is to make the commune prosper, and to keep the commune in order is to ensure abundance and good government throughout the whole country.

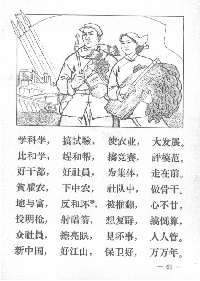

This parody of the Three Character Classic ends with a page reminiscent of the refrain voiced forcefully in the original: the idea that only arduous study will bring success and development. Here, the acquisition of a new type of knowledge, scientific knowledge, is written into the foreground: “If we study sciences and carry out experiments, then we will be able to instigate great change in the countryside” (学科学搞试验使农业大发展), says the text. The general message, however, remains true to the original: here as there, the Three Character Classic calls for devoted study and practice, it calls for competition and for emulating models who, now in the form of good cadres and commune members, should go forward and lead the people to happiness (比和学赶和帮搞竞赛评模范. 好干部好社员为集体走在前). The element of competition might be a new emphasis in this Three Character Classic (it is also taken up in the Three Character Classic on Husbandry, where one of the illustrations shows how a commune member is being presented with an award for good service [1963, 25]), but striving to emulate models is, of course, a pattern well familiar from the original Three Character Classic.

The argument is underlined by an image expressing the morale of this new Three Character Classic: it glorifies the peasant, who is inspired through the right kind of learning (ill. 3.9). In the background a tractor (again) moves in lush fields, below a large dam. Farther in the background stand a series of electronic masts, a factory, and, looming large above all of these, three banners invoking, albeit slightly anachronistically, the three “Red Banners” of Socialist Construction, the Great Leap Forward, and the People’s Communes. In the foreground are two peasants—one female, one male, both with the typical strong features of a large face, huge hands, and tough forearms, pictorial markers that would continue to dominate propaganda publications throughout the Cultural Revolution.

The two peasants are wearing Chinese-style shirts, with Chinese-made buttons. He wears a Mao cap, she a scarf around her hair. Both have, attached to their shirts, a peony, which is a sign of distinction and abundance in traditional symbolism, marking them as peasant heroes. She is holding huge bushels of plants and a hoe in her hands; he is holding, in his left hand, the first edition of Mao’s Selected Works (which contains Mao’s most important writings about peasants). Mao’s book is the focal point of the image. It epitomizes the learning emphasized in the text: it is Mao Zedong Thought, scientific and progressive, that will lead these two peasants (and all Chinese peasants) forward to an ever brighter future. As they gaze toward the book, they have already started moving in the right direction.