Illustration:

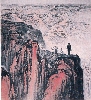

ill. 5.34 (set: 5.34)

Author:

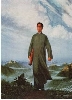

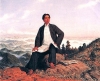

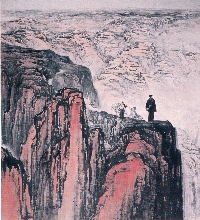

Shi Lu (1919-1982) 石鲁

Date:

1959

Genre:

painting

Material:

scan, paper, colour; original source: ink and color on paper

Source:

Andrews 1994: Andrews, Julia. Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1979. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994:plate 3, insert between 200-201.

Courtesy:

University of California Press, Berkeley

Keywords:

guohua 国画, Chinese landscape painting, critizised painting, mountains, peasants, backwards, not Cultural Revolution standard, dark sky

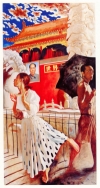

Shi Lu: Fighting in Nothern Shaanxi (Shi Lu: Zhuanzhan Shanbei 石鲁: 转战陕北)

During the first half of the Cultural Revolution one would not encounter in official productions of propaganda posters works in the style of Shi Lu’s 石鲁 (1919-1982) famous and daring Fighting in Northern Shaanxi 转战陕北 of 1959, as seen here. It was commissioned for the Museum of Chinese Revolutionary History and criticized for the first time in 1964. The painting constitutes Shi Lu’s very personal reinvention of national-style techniques: the medium, ink and colour on paper, and the subject matter, landscape painting, was traditional, the large square format, of the painting, and the bright colouring, was new.

Shis conception—typical of the idea of 写意, i.e. “writing ideas” as practiced in traditional Chinese painting—that the loftiness of man, or rather, Mao, might be reflected in his setting, comes straight from the Chinese tradition (Andrews 1994:237/238, see also Hawks 2003:296-301). According to Julia Andrews, in this image, “Mao takes on the monumental persona of the vast, rugged ranges that stretch to the horizon.” (Andrews 1998:231) Yet, Mao also appears, in this image, off-centred, a tiny figure among huge and majestic mountains, isolated on a cliff to the right of the picture, isolated also from the peasants visible near him (significantly, only one of them actually beams toward Mao).

Mao is perhaps deliberating his next move here, in a portentous pose, rarely if ever seen during the Cultural Revolution, but one that can be traced back to the Chinese literati tradition of painting, especially from Song times: with his back towards the viewer (Hawks 2003:296-301)—a position which, as we have seen, is taken up again by Wang Xingwei in his parodies on Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan (ill. 5.27). Mao’s pensiveness, the irresolute, wavering mood of the depiction, the dominance of black colour, is decidedly not in accord with Cultural Revolution standards which would insist on a bright style and would cover up the dirt and some of the hardships entailed by heroism which clearly still hover in the somewhat heavy-handed background in this painting (Andrews 1998:235).