Illustration:

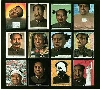

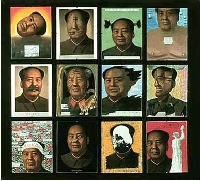

ill. 5.43 (set: 5.42)

Author:

Zhang Hongtu (1943-) 张宏图

Date:

1989

Genre:

photo collage

Material:

internet file, colour, original source: 12 units - photo collage, acrylic on paper, 8.5 x 11 inch each

Source:

Zhang Hongtu, Chairmen Mao, 1989 (DACHS 2008 Zhang Hongtu http://momao.com/), Heidelberg catalogue entry

Courtesy:

Zhang Hongtu

Keywords:

Mao Zedong, Mao portrait, Tian’anmen Square, student protests, Goddess of Democracy, sun, red sun, Serve the People, repitition, demonstrators, parody, Red Guards, Red is The East, Internationale, Li Lu

Zhang Hongtu: Chairmen Mao (Zhang Hongtu: Mao Zhuxi 张宏图: 毛主席)

The question of meaning and the questionable pastness (or emptiness and thus, insignificance) of Mao’s presence returns for a good decade in Zhang’s works. His 1989 depiction of twelve Chairmen Mao, arranged in three rows of four, makes the viewer see a number of defaced, denatured, childlike and comic Maos, Mao upside down, Mao out of focus or fading, Mao distorted, with his nose and eyes exchanged or the two parts of his face swapped; Mao disembodied, just his head rolling around—glowing like the sun, though; Mao like a toddler with the traditional short braids; Mao naked, with his fatty breasts hanging; Mao with a tiger mask, and Mao with a Stalin-beard. The series also includes Mao lecherously ogling the Goddess of Democracy (with “women” in the speech bubble), and Mao with a headband “Serve the People” before a background of banner-waving student demonstrators in Tian’anmen Square, 1989. Mao appears as always the same old Mao, and thus, in repetition, the image is a reminiscence of the staged (not just Cultural Revolution) processions well familiar to the audiences looking at this picture.

He is presented in many different forms and from many different perspectives, however: some of the images choose standard formats, are framed and centred, others make the portrait appear skewed or even cut off parts. The artwork may be considered blasphemous and satiric, but it does not speak an unambiguously critical language. The surreal qualities of the work present the Mao one may perhaps encounter in dreams and nightmares, and one such dream would be of him during the demonstrations on Tian’anmen in 1989.

The connection with the Tian’anmen demonstrators made in the final set of four portraits is perhaps most difficult to read: Is Mao seen as a hypocrite or as a real supporter of their ideas? What does it mean that he apparently fancies the Goddess of Democracy (is his ogling and his thought “women” reduced to sexual innuendo or does he like her philosophy, too)? Does he support the demonstrators (who so look like Red Guards, whom he openly supported by wearing their arm band) when he is shown as “one of them” with his headband? Is he part of an alternative dream for Tian’anmen, or is he made responsible for the nightmare it became for many?