Illustration:

ill. 5.70 (set: 5.70)

Date:

1966-1976

Genre:

poster, propaganda poster

Material:

internetfile, colour; original source: poster, colour, techniques: etching, electrostatic flocking, printing

Source:

Wenge yiwu 2000: Wenge yiwu shoucang yu jiage 文革遗物收藏与价格 (An archive and price list of relics from the Cultural Revolution), edited by Tie Yuan 铁源, Beijing: Hualing, 2000:27.

Inscription:

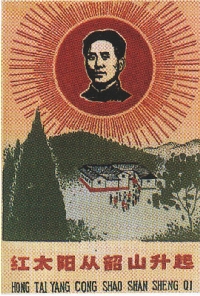

红太阳从韶山升起

HeidICON Image ID:

52805

Keywords:

Mao Zedong, Mao portrait, young Mao, Mao´s home, Mao Cult, Shaoshan Cult, rising sun, sunrise, red sun, hero, propaganda poster, symbolism, sunrays, trees

The Red Sun is rising in Shaoshan (Hong taiyang cong Shaoshan shengqi 红太阳从韶山升起)

Many of the very early Cultural Revolution Shaoshan badges and posters depict a rising sun over Mao’s home, and thus give a symbolic and at the same time quasi-religious rendering of the origins of communism (as here, in ill. 5.70). They reappeared in the 1990s, accompanied by the appropriate stories, one of which is still told, even among youngsters who only barely had memories of the Cultural Revolution if at all (aged 25-35 in 1993, thus born between 1968 and 1978): “They claimed, for example, that at the time of his birth a flash of red light was seen in the sky; again, a comet fell from the heavens when he died” (Barmé 1996:265).

Visitors to Shaoshan in the 1990s would “burn incense and paper money, and set off firecrankers before the statue bronze Mao 6 meters, erected in the village square. Some kowtow to Mao as if he were a God who could grant a good fortune” (Landsberger 2002:162). The practice continues: in 2008 during a “night without sleep” 不眠夜 to commemorate Mao’s 115th birthday on December 26th, visitors burned incense, bowed in front of Mao’s statue, and sang Red Is the East, leading processions with the Little Red Book and huge portraits of Mao all through the streets of Shaoshan (DACHS 2009 Mao Memory).

On April 2nd, 2009 alone (during the Qingming Festival for remembering the dead), some 30.000 people visited Mao’s birthplace Shaoshan (DACHS 2009 Mao Nostalgia). A recent survey also found that “11.5% of the families surveyed had a shrine in their homes of Mao, in the form of a statue or bust. This was only slightly less than the number of families (12.1%) that keep memorial tablets of their ancestors.” (ibid.)

Knowing this, it might not be surprising to discover that the religious element continues to play an important role in MaoArt to the present day. The message of those images created after Mao may be ambivalent: Mao the sun, savior, and god is one possible meaning, but the images also allow for, or even evoke, different interpretations. (See also HeidIcon 52805).