Illustration:

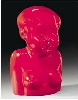

ill. 5.83

Author:

Yin Zhaoyang (1970–) 尹朝阳

Date:

2006

Genre:

painting, oil painting

Material:

internet file; original source: oil on canvas, signed, 78 x 65 cm

Source:

Yin Zhaoyang, Mao, DACHS 2008 Mao Images, 117, Heidelberg catalogue entry

Courtesy:

Yin Zhaoyang

Keywords:

Mao Zedong, Mao memories, icon, idol, Mao’s image, contemporary China, personal significance, Chinese avantgarde, defiance, Mao Cult, identification, mimicry, satire, representation

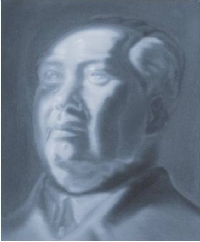

Yin Zhaoyang: Mao (Yin Zhaoyang: Mao 尹朝阳: 毛)

MaoArt by younger artists such as Zhu Wei, Wang Xingwei, or Zhang Chenchu illustrates that for them, too, Mao is not “reduced to an icon in the popular sense of the term, an idol with a visual relevance similar to that reached in the West by Marilyn or Elvis.” He is not just “an item of wall decoration or an image without depth that does not retain any personal significance” (DalLago 1999, 51). On the contrary, defining Mao remains part of defining one’s self to many Chinese artists (and non-artists alike, as the blog reactions to “defamations” of Mao’s image discussed above illustrate). Even substituting Mao with the self is one such act of defiance (see Barboza and Zhang 2009).

These artists are thus as much performed by Mao as they purposely perform Mao. His image becomes a sign onto which, as is often the case in the system of celebrity cults, the viewer may “overlay his or her own interpretation ... with his or her own sexual, personal and cultural identity” (DalLago 1999, 51). Quite accordingly, Zhu Qi writes about Yin Zhaoyang 尹朝阳 (1970–) and his unfocused 2006 portrait of Mao in grey colors (which is reminiscent of ill. 5.31a & ill. 5.31b) to be seen here:

"Forget that Yin was born in 1970’s and only caught the last rays of the setting sun that was Mao. No one before or after Mao’s death was really able to escape his indelible influence, at once one for awe and respect. But Yin’s representations did not stop with that. Unlike those previous generations who lost their own identity in their fervent worship of Mao, Yin’s art produced two distinct identities: one being Mao, the other his own. Of course, they were not “equal.” One clearly overshadowed the other like an eclipse. But the background of their lively union was always the problematic of self, the question of destiny, the tapestry of human nature itself. With one mind they faced each other on the canvas, locked in a fatal strategy of mutual mimicry. This went well beyond the baseline of homage, portraiture, and even representation, even as it cast a sidelong glance at the forms of symbol play and post-ideological satire. Observation of Mao and Mao mimicry have been important ways of transcending the common boundaries of self throughout recent history. Yin Zhaoyang has certainly used the image of Mao to carry out an investigation into the possibilities of self. This investigation has two sides. First, it is acknowledgement of influence to a greater or lesser degree. On the other hand, it is tacit admission that one has entered into the same trajectory as Mao and is hurtling toward the same teleological endpoint. And it is this subtle point which distinguishes Yin’s paintings from others which are tirelessly implicated in simple self-proliferation. His paintings, rather, systemically represent a kind of meta-self. And within this context each step acts in concert with the preceding step, each completed image echoes the psychology of the moment, which in turn gives new resonance to each completed image. Such a strategy precludes any sort of quest for the origins of Mao or the originary nature of self. Rather what is offered is a kind of sacrament to human nature. It is an experimental act of representation." (Zhu 2007, 20)