Mao out of Focus

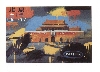

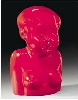

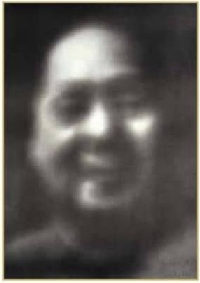

While Luo’s depiction of Mao was made before the strict formulation of orders how best to paint this portrait (so that the elephant would no longer look like one, ill. 0.0), Yan Peiming’s (1960-) 1992 portrait of Mao 毛 seen here, on the other hand, not unlike the controversial portrait of the dying Mao with his successor Hua Guofeng (ill. 5.22), must be read as a deliberate answer to Cultural Revolution standards.

And indeed, Yan Peiming would say that his training was in propaganda art: “In China, I learned propaganda painting and in principle I still paint in that style” (China Avant-Garde 1994:171). In his image, we have a combination of cold colours, and heavily emphasized brushwork which renders Mao’s face anything but smooth. All of this would already have made this work completely unacceptable during the Cultural Revolution. The fact that it is not only “slightly out of focus” makes it worse, of course.

The image reminds a European audience of a 1968 counterpart (ill. 5.31b) by Gerhard Richter (1932-) who depicts Mao through a haze which equally disfigures, better, transfigures him. Both his and Yan Peiming’s image point to the complicated relation between our sensual perception of reality—which is always a perception limited—and reality itself (it is “not like that”). The “defacing,” almost abstract manner in which the face is designed in both cases makes it into a strong—if ambiguous—statement about Mao past and present. Yan’s image is even more ambiguous, because the implied audience of an image like this is one not just appreciative of modernist style, not just revelling in his almost complete disappearance behind the haze, but one also, for whom Mao is still an imposing personality, in every sense of the word: the painting is huge, 2 by 3 metres.