Mao Portraiture in National Style

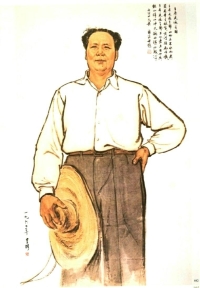

During the first half of the Cultural Revolution, one sees no newly publicized compositions of MaoArt in a style comparable to that of Li Qi’s 李琦 (1928-) 1958 painting Mao at the Ming Tombs Reservoir 在十三陵水库工地上 (ill. 5.32a), or his oft-quoted 1960 image of Mao with the straw hat, with the significant title, The Chairman goes Everywhere 主席走遍全国 (ill. 5.32b). Both paintings are in so-called guohua style 国画 (national style), retaining the loosely-brushed qualities of traditional painting, the first even inclusive of a four-word archaizing poem—praising how under Mao’s rule “all hearts (are) united” 心连心 (ill. 5.32a).

In these paintings, traditional techniques are used for the depiction of contemporary social settings. In Mao at the Ming Tombs Reservoir, for example, industrial labour is depicted and mighty cranes substitute for dainty trees before an albeit very typically depicted Chinese-style landscape. The image shows Mao’s ritualistic emergence into labour in May 1958, with shovel in hand, a worker offering him a sweat towel and other workers standing by, watching the scene happily. Many images like these have been produced in the 20th century.

Here, Mao is the central focus, his position is slightly elevated with regard to all other protagonists. Accordingly, in terms of structural composition, there would have been no trouble for this picture during the Cultural Revolution, yet oral history suggests that Li Qi’s 1960 picture of Mao with a straw hat remained a visual presence throughout the Cultural Revolution decade (ill. 5.32b).

Li Qi himself, did not fare so well: not only had he painted portraits of Liu Shaoqi which became dangerous for any Chinese artist in the early years of the Cultural Revolution (Andrews 1994: 328), but the very “aristocratic” style of “national-style” painting which he employed, painting with traditional Chinese pigments on traditional Chinese paper, was, at least officially, condemned during the early years of the Cultural Revolution (Hawks 2003).