Godlike Mao

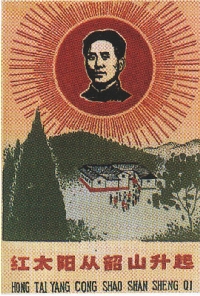

Many of the very early Cultural Revolution Shaoshan badges and posters depict a rising sun over Mao’s home, and thus give a symbolic and at the same time quasi-religious rendering of the origins of communism (ill. 5.70). They reappeared in the 1990s, accompanied by the appropriate stories, one of which is still told, even among youngsters who only barely had memories of the Cultural Revolution if at all (aged 25-35 in 1993, thus born between 1968 and 1978): “They claimed, for example, that at the time of his birth a flash of red light was seen in the sky; again, a comet fell from the heavens when he died” (Barmé 1996:265).

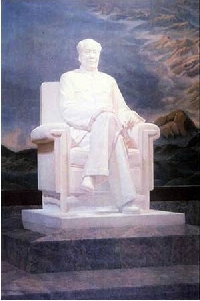

Visitors to Shaoshan in the 1990s would “burn incense and paper money, and set off firecrankers before the statue bronze Mao 6 meters, erected in the village square. Some kowtow to Mao as if he were a God who could grant a good fortune” (Landsberger 2002:162). The practice continues: in 2008 during a “night without sleep” 不眠夜 to commemorate Mao’s 115th birthday on December 26th, visitors burned incense, bowed in front of Mao’s statue, and sang Red Is the East, leading processions with the Little Red Book and huge portraits of Mao all through the streets of Shaoshan (DACHS 2009 Mao Memory). On April 2nd, 2009 alone (during the Qingming Festival for remembering the dead), some 30.000 people visited Mao’s birthplace Shaoshan (DACHS 2009 Mao Nostalgia). A recent survey also found that “11.5% of the families surveyed had a shrine in their homes of Mao, in the form of a statue or bust. This was only slightly less than the number of families (12.1%) that keep memorial tablets of their ancestors.” (ibid.)

Knowing this, it might not be surprising to discover that the religious element continues to play an important role in MaoArt to the present day. The message of those images created after Mao may be ambivalent: Mao the sun, savior, and god is one possible meaning, but the images also allow for, or even evoke, different interpretations.

Reproduction and repetition were important hallmarks of Cultural Revolution Culture. They helped confirm the godlike qualities of MaoArt. Pre-and post-Cultural Revolution MaoArt, on the other hand, still practices and makes use of the same mechanisms and motifs of reproduction and repetition, but here repetition is not necessarily affirmative. It can be subversive, too. Now, repetition and reproduction serve the purpose not of redundantly multiplying one and the same but of diversifying several possible meanings and interpretations: Mao is associated with holiness, if not religious frenzy: it is also questioned time and again whether he still is a god (or ever was).

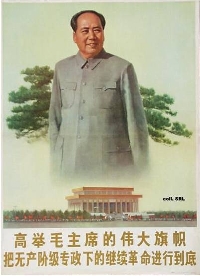

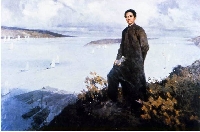

These contradictions notwithstanding, the visual evidence speaks another language: Godlike Mao lives on long after his death, still towering above everyone and everything as in a 1977 propaganda poster, where he is shown suspended above the monumental memorial hall completed in the summer of that same year: Hold High the Great Banner of Chairman Mao and Carry on till the End the Continuous Revolution under the Dictatorship of the Proletariat (高举毛主席的伟大旗帜把无产阶级专政下的继续革命进行到底) (ill. 5.71). Mao remains an imposing presence, white and brilliant as the sun, in his 1978 memorial statue Mao Will Always Live in Our Hearts (毛主席永远活在我们心中) (ill. 5.72). And up in the clouds, overlooking the vast landscape, he does look rather similarly transcendent and detached as in Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan in another depiction given the appropriate title Who Is in Charge of the Universe (问苍茫大地谁主沉浮), painted by Chen Yanning 陈衍宁 (1945–) in 1978 (ill. 5.73).