Illustration:

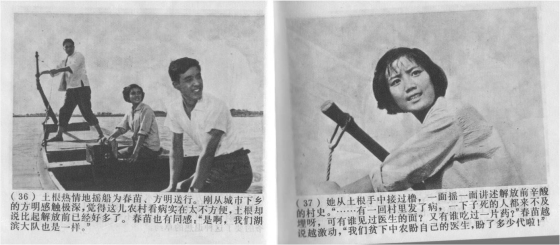

ill. 6.30 (set: 6.30)

Author:

From film to Comic: Wang Zuyi 连环画改: 王祖毅

Date:

1976

Genre:

comic, comic strip, comic based on film

Material:

scan, paper, grayscale; original source: photographs print on paper, black-and-white

Source:

Chunmiao 春苗 (Chunmiao). Shanghai: Shanghai renmin, 1976:36/37.

Keywords:

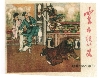

Cultural Revolution, love, romance, Chinese Communist Party, boat, punting, hero, heroine, relationship, representation, iconography, waves, Chunmiao

Spring Sprouts (Chunmiao 春苗)

A denial of sexuality is the rule in comics published during the second half of the Cultural Revolution. Accordingly, love stories that were once included in the plots are excluded or completely subdued; scenes in which sexuality, nudity, or even love or sentimentalism might play a role are eradicated. According to a summary of the “Forum on the Work in Literature and Art in the Armed Forces with which Comrade Lin Biao Entrusted Comrade Jiang Qing” (林彪同志委托江青同志召集部队文艺工作座谈纪要), sentimentalism, and especially romantic love between men and women, was taken to be bourgeois (Hongqi 1967.9:19–20).

The white-haired girl in the 1971 comic (as well as in the earlier model ballet), is no longer raped by her landlord’s son, and her romantic relationship with her fiancé Dachun is subdued, although always latent, in spite of continual erasure in successive revisions of the plot before and during the Cultural Revolution (Meng 1993): when they beam together in happiness, in the final and concluding picture, they still exude the togetherness worthy of a couple just married (see ill. 6.8). This ending is an example of what Wang Ban (1957–), who experienced the Cultural Revolution as a sent-down youth in the countryside, describes as follows:

"Despite its puritanical surface, Communist culture is sexually charged in its own way. High-handed as it is, Communist culture does not—it cannot, in fact—erase sexuality out of existence. Rather, it meets sexuality halfway, caters to it, and assimilates it into its structure." (Wang 1997, 134)

Others echo his observations: “If you talk about love, then you don’t love Mao; that was the idea. But it is impossible to tell a people not to talk about love, so everybody will do so in secret.” (Playwright, 1956–). While underground art and literature reversed official restrictions quite openly, even official art did not completely eradicate love either, and love most certainly played a role in the perception of these works as well. Sexual desire remains present as a continuous and unmistakable undercurrent in these comic stories.

Subdued, covert, but still omnipresent appears the relationship between Fang Ming, the doctoral student at the village hospital, and Chunmiao, the barefoot doctor, in the 1976 comic Spring Sprouts. When Fang Ming and Chunmiao are shown together on a boating trip or working side by side with great eagerness and interest, their (class-based) love is only latently evident since it is only love for the Party, not for a potential sexual partner, that counts during the Cultural Revolution.