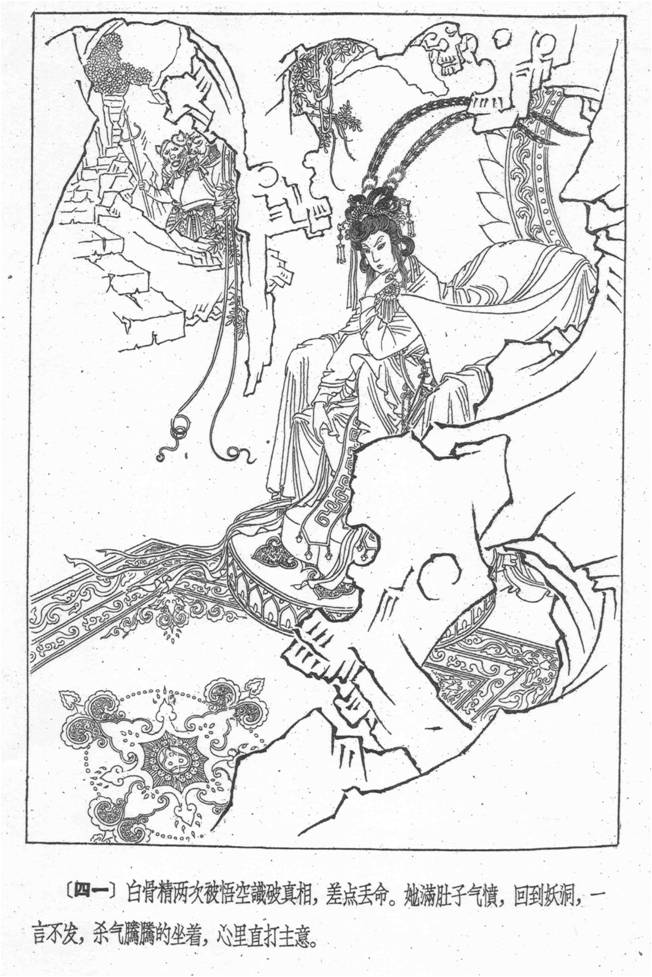

Illustration:

ill. 6.41 a (set: 6.34)

Author:

Zhao Hongben (1915-2000) 赵宏本

Date:

1962

Genre:

comic, comic book, comic strip

Material:

scan, paper, black-and-white; original source: woodblock print

Source:

SWKSDBGJ 1962: Sun Wukong san da baigujing 孙悟空三打白骨精 (Sun Wukong thrice defeats the white-boned demon). Shanghai: Shanghai meishu, 1962:41.

Keywords:

White-boned Demon, demon, visualisation, villain, depiction, heroism, Sun Wukong, Journey to the West, Cultural Revolution, criticism, comic

Zhao Hongben: Sun Wukong thrice defeats the white-boned Demon 1962 (Zhao Hongben: Sun Wukong san da baigujing 赵宏本: 孙悟空三打白骨精)

The demon is also placed more toward the corner and looks more cruel (ill. 6.41a&b), or is seen from the side rather than the center (see ill. 6.41c&d). All of this serves to deemphasize the demon’s visibility and thus to elevate Monkey King to greater prominence. Nevertheless, with regard to the villains, the number of changes is rather insignificant in view of the comic’s radical critique.

Thus, even the modified 1972 re-publication of the comic is by no means in accordance with every aspect of the Cultural Revolution straightjacket. It is a Maoist allegory, but it appears in traditional attire, praises Mao’s thought only implicitly, if at all, features feudal thought and heritage (especially Buddhism), and still, in spite of the revisions, does not really showcase its heroes. Nor does it vilify the villains as much as an “ideal” Cultural Revolution Comic would. It is published nevertheless. Once more, the power of much-decried “centralized bureaucratic planning” (see Farquhar 1999, 212) in the comic (and, more generally, the cultural) industry during the Cultural Revolution is to be questioned.

Although the production of Zhao Hongben’s original Sun Wukong comic had been suspended during the first years of the Cultural Revolution, the second half of the Cultural Revolution saw its almost integral recovery (and the lack of nipples and navel to which Zhao Hongben agreed in revising his comic could, in this context, perhaps even be read ironically). Significant differences between standards of cultural production in the late 1960s and the early 1970s can be seen, then. Why else would Zhao Hongben’s comic first be criticized and then published? Clearly, the Cultural Revolution straightjacket was not as straight as one may have assumed it was.