ill. 6.32 a, metadata

ill. 6.32 a, metadata

ill. 6.32 b, metadata

ill. 6.32 b, metadata

ill. 6.33 a, metadata

ill. 6.33 a, metadata

ill. 6.33 b, metadata

ill. 6.33 b, metadata

ill. 6.33 c, metadata

ill. 6.33 c, metadata

Red Guard Comics

The early years of the Cultural Revolution saw almost no official publications of new comics. While during the 1950s several hundreds of new titles were published every year, this number went down dramatically and came to an almost complete standstill after 1966. It began picking up only since after 1970, when at first a good 100 and soon several hundreds of new titles appeared every year (Hwang 1978; Seifert 2001; Seifert 2008).

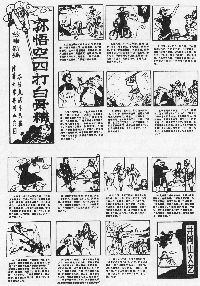

While the comic presses did not publish much officially, then, in the first half of the Cultural Revolution, a flood of comic strips and caricatures appeared in Red Guard newspapers and pamphlets. In February of 1967, for example, the Red Guard newspaper Jinggangshan wenyi (井冈山文艺) published a parody of Sun Wukong Thrice Defeats the White-Boned Demon (ill. 6.32a, see Wagner 1990, 200-204). Here, the white-boned demon, identified with Liu Shaoqi who was criticized as the “Chinese Krushchev” in the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, is defeated not just three but four times (孙悟空四打白骨精). The Red Guard comic chooses a traditional theme, making it an “old comic” and thus not quite in line with the straightjacket. But it does so in order to attack revisionism, a strategy which was well in line with the policies of the time.

The Red Guard comic declares the white-boned demon to be the major revisionist. This is very apt, as Liu Shaoqi was indeed considered the greatest enemy in early Cultural Revolution political rhetoric. On the other hand, the comic still has Zhu Bajie appear lasciviously: with nipples and navel in full shape and form (6.32b). The comic thus openly subverts the straightjacket, and to do so in 1967 would have chained in some, bringing them into labor service. But the rules were not equally applied across the board, especially to those who called themselves “Mao’s Soldiers.”

And there is more to be said about this: Admittedly, in the Red Guard comic, the sun shines at the right time, with our main hero Monkey King victorious at the optimistic end (ill. 6.33c, panel 21). But the hero is still not depicted in the prominent manner he would deserve according to the rule of Three Prominences. Indeed, one could argue that it is the demon who achieves greater prominence, for in his/her different incarnations he/she actually receives more close-up shots than does Monkey King.

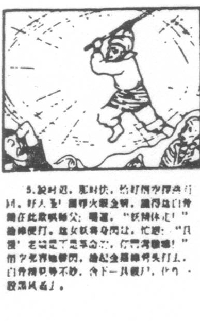

Moreover, the other characters, too, Zhu Bajie most prominently among them, are shown almost as many times as Monkey King, which again serves to diminish his prominence. Although Monkey King is victorious in the end and seen as a centralized or superior figure in some of his fights with the demons (ill 6.33a&c), this is not always the case in all panels. Indeed, there are several instances in which his fighting abilities do not appear superior and he is almost squeezed out of the picture by his enemy (ill. 6.33b).

Thus, even in heady 1967, undoubtedly one of the most politicized periods of the Cultural Revolution, the regulations of Cultural Revolution Culture could or would not be applied consistently. This period, which has often been characterized as one of absolute dictatorship and monolithic rule over Chinese art and culture, is rather more anarchic than is generally assumed.