ill. 6.34 a, metadata

ill. 6.34 a, metadata

ill. 6.34 b, metadata

ill. 6.34 b, metadata

ill. 6.35 a, metadata

ill. 6.35 a, metadata

ill. 6.35 b, metadata

ill. 6.35 b, metadata

ill. 6.36, metadata

ill. 6.36, metadata

ill. 6.37 a, metadata

ill. 6.37 a, metadata

ill. 6.37 b, metadata

ill. 6.37 b, metadata

ill. 6.37 c, metadata

ill. 6.37 c, metadata

ill. 6.38 a, metadata

ill. 6.38 a, metadata

ill. 6.38 b, metadata

ill. 6.38 b, metadata

ill. 6.39 a, metadata

ill. 6.39 a, metadata

ill. 6.39 b, metadata

ill. 6.39 b, metadata

ill. 6.40 a, metadata

ill. 6.40 a, metadata

ill. 6.40 b, metadata

ill. 6.40 b, metadata

ill. 6.41 a, metadata

ill. 6.41 a, metadata

ill. 6.41 b, metadata

ill. 6.41 b, metadata

ill. 6.41 c, metadata

ill. 6.41 c, metadata

ill. 6.41 d, metadata

ill. 6.41 d, metadata

Monkey Changes between 1962 and 1972

In 1972, Zhao published his Monkey King comic in revised format (Comics SWKSDBGJ 1972). Some inconsistencies can be observed: although this version does include a number of changes from 1962, the missing navel and nipple being the most obvious, it contains few other changes and certainly does not remedy completely the points accused and criticized by Red Guards in the early years of the Cultural Revolution. The republished version thus illustrates once more that the straightjacket for cultural production in the Cultural Revolution had its loopholes.

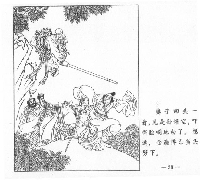

Admittedly, Sun Wukong had, in this more recent version, gained some heroic features: no longer does he appear as a supplicant, for example, in front of Tang Seng who dismisses him for killing the different incarnations of the demon (because a true follower of Buddha is not allowed to kill). In the revised version, Sun is the one who takes center stage and who appears much larger and stronger than everyone else, facing the viewer, while his companions are shown from the back or from the side (ill. 6.34a&b).

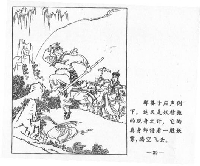

Similarly, some of the panels from the 1962 version in which he is told off or punished by Tang Seng are simply omitted or substituted to make him look better; he is never punished in the new version and he is never humiliated such that he has to stand on a lower level than everyone else. An image from the earlier version in which the monk is seen with his entourage looking down at Monkey King from a cliff and casting a punishing spell on him as he bends down awkwardly in pain (ill. 6.35a) is substituted with an image in which Monk Sha is now seen advising Tang Seng not to punish Sun. In this substitute image, Sun appears, significantly, in the center top, with his companions pushed to the side (ill. 6.35b).

The fact that he, Sun Wukong, is the only one who understands who is demon and who is human is mentioned in the text. It is made much more evident pictorially than before, by showing him in central advisory functions in additional panels (ill. 6.36). Monkey’s exclusive claim to enlightenment is specifically mentioned in the preface to the 1972 edition, which emphasizes that while the monk is ultimately “educated by reality” Monkey shows wisdom, bravery, resolution and a priori knowledge. Unlike everyone else, he knows that “when you see a demon, you must wipe it out.” The 1972 version of the comic teaches that only complete reliance and blind belief in Sun Wukong (that is, Mao Zedong) enables one to discover the demons; the more appealing a proposal or theory may seem, the greater the probability that it is nothing but a demonic device used by “revisionists” to subvert the Maoist line (see Wagner 1990, 195–96).

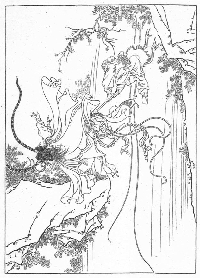

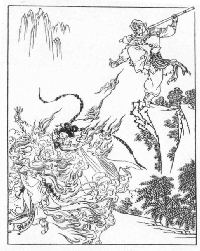

In the 1972 version, Sun Wukong is equipped with greater and much more dramatic fighting presence than in the earlier version. The panels are modified such that Monkey King becomes the dominant focus. In one case, for example, the background is reduced in order to make more space for more of Sun Wukong (ill. 6.37a&b). Moreover, a second panel is added to the scene, putting him, who has just defeated the old woman demon, in dramatic pose, squarely in the center (ill. 6.37c). The new version of a final fight with the demon shows Sun changed into five monkeys not only once but repeatedly (Comics SWKSDBGJ 1972, 112). This panel further substitutes a panel from the original version in which Monkey King is seen from the back, and actually has him kill the demon much more dramatically in a fire (ill. 6.38 a&b). Comparatively speaking, however, and although each of the added eight panels is to his credit, Sun does not gain all that much from revisions on his behalf.

The demons, on the other hand, are not made significantly uglier or less impressive in 1972: the young woman remains the same (ill. 6.39a&b), the old woman only gains a little in ugliness through a close-up depiction (see ill. 37a&b), and the old man is made to appear a little more helpless when his death is shown from behind rather than from the front (ill. 6.40a&b). The number of scenes in which the demon appears central is reduced in the later version. Two panels (9&10) are exchanged for this purpose.

The demon is also placed more toward the corner and looks more cruel (ill. 6.41a&b), or is seen from the side rather than the center (ill. 6.41c&d). All of this serves to deemphasize the demon’s visibility and thus to elevate Monkey King to greater prominence. Nevertheless, with regard to the villains, the number of changes is rather insignificant in view of the radical critique with which this comic had been faced.

Thus, even the modified 1972 re-publication of the comic is by no means in accordance with every aspect of the Cultural Revolution straightjacket. It is a Maoist allegory, but it appears in traditional attire, praises Mao’s thought only implicitly, if at all, features feudal thought and heritage (especially Buddhism), and still, in spite of the revisions, does not really showcase its heroes. Nor does it vilify the villains as much as an “ideal” Cultural Revolution Comic would. It is published nevertheless. Once more, the power of much-decried “centralized bureaucratic planning” (see Farquhar 1999, 212) in the comic (and, more generally, the cultural) industry during the Cultural Revolution is to be questioned.

Although the production of Zhao Hongben’s original Sun Wukong comic had been suspended during the first years of the Cultural Revolution, the second half of the Cultural Revolution saw its almost integral recovery (and the lack of nipples and navel to which Zhao Hongben agreed in revising his comic could, in this context, perhaps even be read ironically). Significant differences between standards of cultural production in the late 1960s and the early 1970s can be seen, then. Why else would Zhao Hongben’s comic first be criticized and then published? Clearly, the Cultural Revolution straightjacket was not as straight as one may have assumed it was.