Illustration:

ill. 0.0

Author:

Wang Zhuqi 王者琦

Date:

1978

Genre:

comic, comic strip

Material:

scan, paper, black-and-white; original source: print on paper, black-and-white

Source:

LHHB 1978.9:37.

Inscription:

画象记 好!好!好! 粉碎四人帮 大快人心! 文艺的春天来了!

Keywords:

Jiang Qing, satire, parody, Cultural Revolution, Gang of Four, Mao Portrait, cultural policies, comic, Mao Zedong, Mao´s image

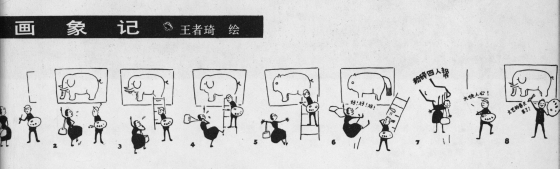

Record of Painting an Elephant (Huaxiangji 画象记)

This comic strip appears in the fall of 1978, in the comic magazine Lianhuan huabao 连环画报. It is entitled 画象记 “Record of Painting an Elephant” and features two persons, an unnamed painter and Jiang Qing 江青 (1914-1991), Mao’s wife who took charge of cultural production during the Cultural Revolution and whose name is added in the first image, to make sure that she will be recognized by every reader (panel 1).

The painter has outlined an elephant which, as the strip continues, goes through a number of revisions, each following Jiang Qing’s angry orders (panels 2-5). At the end, the elephant looks no longer anything like an elephant. At this point, Jiang Qing is seen jumping around with excitement, just like a little child, crying out “Good! Good! Good!” while the painter looks quite baffled (panel 6).

The next image under the motto 粉碎四人帮 “Smashing the Gang of Four” shows a large fist banging down on and suffocating Jiang Qing, while the painter appears quite cheerful and satisfied—the characters above his head read 大快人心 which translates as “making the people happy and content”. He rejoices, as we can see in the next picture (panel 8): “spring has come for the arts” 文艺的春天来了 and quickly retouches his image of an elephant which is now, as in his first attempt once viciously criticized by Jiang Qing (panel 2), quite readily recognizable as an elephant again.

The comic strip plays with homonyms for “elephant” (象 xiang) such as “portrait” (像 xiang) or “auspicious” (祥 xiang). It also plays with the several meanings of the character for “elephant” 象, which can also be read as “to imitate” as in “imitating sound” or “onomatopoeia” (象声), “to be similar/like” as in “serving the people like Lei Feng” (象雷锋一样为人民服务), or “to seem/appear” as in “it seems that it is about to rain” (好象要下雨了).

With this in mind, the comic strip can be read as a record of painting not elephants but portraits (画像记), or rather, of painting the portrait, that is, the portrait of Chairman Mao, the most important hero of the Cultural Revolution. Painting the portrait meant observing numerous strict rules. Failing to observe them, even if one was convinced that the end product was not only not an elephant (不象 bu xiang) but indeed not similar (不象 bu xiang) to its original, i.e., Mao himself, was indeed inauspicious (不祥 bu xiang) to any painter who dared do so. The comic strip is thus an illuminating commentary on (cultural) policies during the Cultural Revolution, policies that made some things appear to be what they were really not, and vice versa.