Illustration:

ill. III.1

Author:

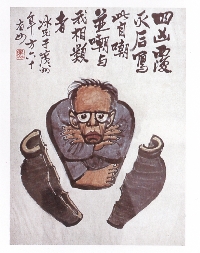

Liao Bingxiong (1915–2006) 廖冰兄

Date:

1979

Genre:

painting, caricature

Material:

scan, paper, colour; original: ink and colour on paper

Source:

Sullivan 1996: Michael, Sullivan. Art and Artists of Twentieth-Century China, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996:plate 63 insert between p.144/145.

Courtesy:

University of California Press Berkeley

Keywords:

Cultural Revolution, caricature, torture, restriction of artistic practice

Liao Bingxong, Himself liberated after 19 years

A recent exhibition at the Guangdong Museum of Art, documented at length in Red Art (红色美术 Hongse meishu), a film by Hu Jie and Ai Xiaoming (Hu and Ai 2007), featured officially sanctioned propaganda posters side by side with some of the modernist and traditionalist art—the exhibition called it the “floating avant-garde” (浮游前卫)—produced during the Cultural Revolution years in spite of all political directives officially forbidding it. The exhibition and its discussion in the film are a remarkable attempt to recover the contradictions of political mandate and artistic creation during this period, a recovery which, in scholarly writing, has only recently begun (Silbergeld and Gong 1993).

In her masterly study Painters and Politics in China, Julia Andrews acknowledges the stubborn habit of referring to the Cultural Revolution as the “ten lost years.” She explains: "For artists such as Ye Qianyu, who was beaten severely by his students and then jailed for nine years, such a formulation would be entirely appropriate. For those such as Lin Fengmian, who kept his work out of Red Guard hands by scrubbing it to pulp on a washboard, even more than one decade of creative activity was lost. The physical and psychological violence inflicted by some Red Guard students on their teachers, their party leaders, and on each other has, understandably, produced a revulsion against any activity associated with the Cultural Revolution. Older artists in particular associate the artistic images of the Cultural Revolution very directly with the torture they suffered. For most young and middle-aged artists, however, the ten “lost years” included a good deal of painting, even if it was not what we might consider high art." (1994, 314, see also Andrews 2010, 40–41)

Nevertheless, many artists probably felt like cartoonist Liao Bingxiong 廖冰兄 (1915–2006) who, in 1979, painted this impressive cartoon image of “Himself Liberated after 19 Years” showing himself breaking out of a vase, but with his body still formed exactly in the shape of the vase, his feet and arms crossed, his mouth dumbfounded. Destruction and restriction of artistic practice accompanied by torture of the artists involved peaked during the Cultural Revolution (Sullivan 1996, 154–55; Yang 1995, 344–47).

Artistic production created according to official standards during the Cultural Revolution was extremely univocal and political during this time—but it never stopped and was accompanied by much that was only unofficial but equally alive. More so than any other political movement before or since, the Cultural Revolution was all sound and words, especially in the countryside—and it was, decidedly, also a visual event. This point is well illustrated in the exhibition discussed in Red Art, which shows, for example, huge propaganda posters (some of which had a width of 25 meters) in situ and follows the rote production of images such as Liu Chunhua’s Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan, of which a mythical 900 million copies are said to have been produced during the Cultural Revolution (Landsberger 2002, 152; Hu and Ai 2007). Cultural production, then, in all artistic fields including the visual arts, was a major element in the Cultural Revolution experience.