Illustration:

ill. III.2

Date:

1974

Genre:

poster, propaganda poster

Material:

scan, paper, colour; original source: poster, colour

Source:

Chinese Propaganda Posters 2003: Chinese Propaganda Posters, edited by Anchee Min, Duo Duo, and Stefan R. Landsberger. Cologne and Los Angeles: Taschen, 2003:3.

Courtesy:

Michael Wolf

Inscription:

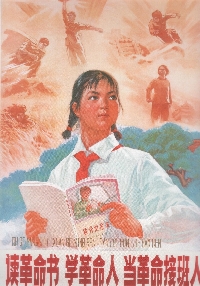

读革命书学革命人当革命接班人

Keywords:

model hero, revolutionary hero, Lei Feng, revolutionary books, Cultural Revolution, local hero, children, Liu Hulan, Huang Jiguang, Dong Cunrui, Cai Yongxiang, poster, martyr, heroism

Read revolutionary Books, learn from Revolutionaries and become an Heir of the Revolution (Du geming shu, xue gemingren, dang geming jiebanren. 读革命书, 学革命人, 当革命接班人.)

Revolutionary China as a visual experience was characterized by constant and repetitive exposure to heroic figures. Reverence for these heroes was implicit as a function in visual presentation. The hero could but be understood as a model for emulation. Thus, it would be repeated on new levels, mise-en-abyme practiced over and over again in order to call for action. The imposing portrait of the nation’s larger-than-life hero, Mao, becomes the inspirational model for the local heroes in the model works, model stories, and model comics. These local heroes in turn become models as portrayed on posters, teapots, cups, and cushions to inspire the individual brigade peasant leader who, again, would be depicted painting a picture or singing a song or telling a story of such a heroic model. And this leader would in turn become a model for each and every one of the peasants in his or her brigade, who in turn would be depicted in a model comic/poster/story as models for all peasants in China, and so on.

One example of this practice at work is this 1974 poster "Read Revolutionary Books, Learn from Revolutionaries, and Become an Heir of the Revolution" (读革命书学革命人当革命接班人). It shows a young girl reading model hero Lei Feng’s diary. Above her head (i.e., in her thoughts) are a number of other revolutionary heroes: Liu Hulan 刘胡兰 (1932–47), the teenage girl who was beheaded by the Nationalists because she would not betray her faith in Communism, on the far right; above the girl the soldier Huang Jiguang 黄继光(1930–52), who with his chest blocked American machine-gun fire in the Korean War; next to him Dong Cunrui 董存瑞 (1929–48) who used his own body as a post supporting explosives when blowing up an enemy bridge; and on the left Cai Yongxiang 蔡永祥 (1948–66) who, as an eighteen-year-old, jumped in front of a train to rescue others.

In Anchee Min’s 闵安琪 (1957–) memory of the poster, she reflects on its power of conviction: "I wanted to be the girl in the poster when I was growing up. Every day, I dressed up like that girl in a white cotton shirt with a red scarf around my neck, and I braided my hair the same way. I liked the fact that she was surrounded by the revolutionary martyrs, whom I was taught to worship since kindergarten. ... I continued to dream that one day I would be honored to have an opportunity to sacrifice myself for Mao and become the girl in the poster. I graduated from middle school and was assigned by the government to work in a collective labor farm near the East China Sea. Life there was unbearable, and many youths purposely injured themselves, for example, cut off their foot or hand in order to claim disability and be sent home. My strength and courage came from the posters that I grew up with. I believed in heroism and if I had to, I preferred to die like a martyr." (Min 2003, 5)