Foreign Music and Traditional Music during the Cultural Revolution

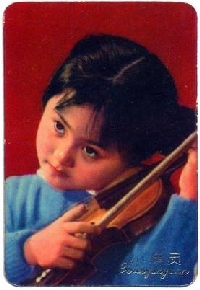

“Get rid of what is stale and bring out the new” (推陈出新) is the title of a calendar produced in 1975. Before a pale blue background, a girl, dressed in a pink sweater, plays the guqin, an age-old seven-stringed Chinese zither (ill. I.1). Another calender from 1975 shows a much younger girl who holds, quite lovingly, a small violin, in itself a foreign instrument to China until the late 19th century: the title of this calendar is “Little Performer” 小演员.

Music, just like all other artistic production, was subject to extreme political reglementation during the Cultural Revolution; only certain correct colors, forms, and sounds were officially acceptable: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91), Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, and Johannes Brahms (1833–97) were condemned due to their “bourgeois” background or upbringing; Arnold Schönberg (1874–1951) and Claude Debussy (1862–1918) were considered “formalists”; Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) were said to be (pre-) representatives of the “revisionist” Soviet regime and thus could not be performed; sounds of the guqin were unacceptable, as they were associated with the “aristocratic” literati of “feudal” China; and traditional Chinese operas were said to bring too many “emperors and ladies,” and too few “workers, peasants, and soldiers” onto the stage. And this list could be continued.

Yet, obviously from these calendar girls, while there were restrictions of the repertoire one could be playing, the playing of foreign and of traditional Chinese instruments actually never stopped completely. And restrictions may not have been felt so acutely either. One contemporary remembers:“Actually, at that time, there were no restrictions as to the playing of either particular instruments or pieces. All the etudes which we played came from the West. We just played everything.” (Artist 1959-).