Media file:

mus. 1.2 a

Title:

Xian Xinghai's Yellow River Cantata (Yellow River Boatsmen's Song) and its Parodies

Source:

Heidelberg catalogue entry, DACHS Archive

Courtesy:

Heidelberg University Institute of Chinese Studies

Keywords:

Yellow River Cantata, Xian Xinghai, workers, peasants, Yan’an

Xian Xinghai's Yellow River Cantata (Yellow River Boatsmen's Song) and its Parodies

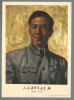

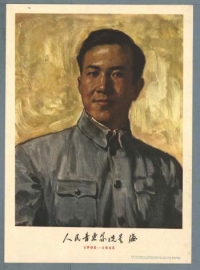

Xian Xinghai 冼星海 (1905–45), hailed as the “People’s Composer” (人民作曲家 Renmin Zuoqujia) after his untimely death in Moscow, had grown up among the fishermen of Guangdong province and had later studied music in Paris. With his “lowly” class background combined with some formal training, he was idealized as being able to synthesize in his music the sentiments of both the (bourgeois) intellectuals and the masses of workers and peasants. This made him an ideal teacher at the Lu Xun Academy in Yan’an, where he taught the young cadres how to compose songs and organize or conduct choral groups (Chen 1995, 19–20).

His most famous composition is the anti-Japanese Yellow River Cantata (黄河大合唱 Huanghe dahechang), composed in 1939. Here, traditional and foreign elements are ingeniously combined or redeveloped. In Xian’s piece, the Yellow River becomes an emblem of the Chinese spirit. Chinese civilization is said to have originated in the Yellow River Valley, and the river’s periodic floods continue to cause much agony and suffering even today. It evokes, therefore, strong, even tragic emotions on the one hand, yet also collective memories of desperate perseverance in the face of adversity on the other, and it is fictionalized as such in much early Chinese poetry (Chen 1995, 1–6).

The cantata was recomposed by star pianist Yin Chengzong 殷承宗 (1941–) during the Cultural Revolution, to become a piano concerto (one of the 18 model works). Set during the Sino-Japanese War, cantata and piano concerto tell the story of the Yellow River, its people, and their determination to fight the Japanese.

While the original composition for chorus carried an emphasis on sorrow (much of it personal sorrow), the Yellow River Concerto emphasizes more national rage, which can be an outlet for personal sorrow: the eight-movement cantata features a much more balanced relation between movements describing the people, the Yellow River, and the people’s determination to fight the Japanese than found in the Yellow River Concerto where two lengthy movements are devoted to defense and rage. The virtuoso concerto format actually serves this purpose quite dramatically.

Both cantata and piano concerto have, since the end of the Cultural Revolution, been performed time and again. The musical excerpts presented here compare how one passage from the Yellow River Cantata, the “Yellow River Boatmen’s Song,” based on Shanxi dialogue singing (山西对口唱 Shanxi duikou chang) and featuring a male choir and a female choir, has been interpreted in a handful of different versions, each derived from a very different time in Chinese history.

The first (mus. 1.2a) is the version presented in the cantata conceived by Xian Xinghai in 1939, the second (mus. 1.2b) is the take the piece is given in the Cultural Revolution piano concerto by Yin Chengzong in 1969, the third (mus 1.2c) is a pop version performed by a group called “Outer Space Singers” (太空人演唱组 Taikongren yanchangzu) in 1995 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Sino-Japanese War.

Each of these versions has its own special flavor. The 1995 version (mus1.2c), published on a cassette tape entitled The Chinese Soul (中国魂 Zhongguo hun), replicates the choral dialogic structure from the folk tradition that had influenced Xian Xianghai’s original conception. Here, the size of the choir and the orchestra is moderate, and the performance tempo is adapted to a very slow and rhythmic but somewhat light mode. The effect of the Chinese melody running throughout this movement is modified through this slow pace and the use of electronic instruments.The heaviness of the 1939 cantata score (mus 1.2a), in contrast, is due to the use of a huge choir, very different from Chinese folk music traditions. The choir is singing in belcanto, which creates a sound effect even further away from Chinese folk soundscapes. A similar heaviness is also present in the 1969 piano concerto version (mus 1.2b), due to the large romantic orchestra employed there for dialogic singing (the piano being the other interlocutor). In the 1995 pop version, this heaviness is lightened through the use of electronic instruments, percussion, and artificial sounds. The piece is presented, so it appears, by a new generation that has long left behind the war and the difficulties of manual labor but still swells with pride in the Chinese nation.