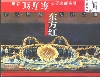

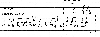

Illustration:

ill. 2.7

Author:

Cui Jian (1961-), Pierre Degeyter 崔健, 皮埃尔狄盖特

Date:

Cui Jian: I Have Nothing: 1986; Pierre Degeyter: The Internationale: 1888

Genre:

sheet music

Material:

scan, paper, black-and-white; original source: music sheet, paper

Source:

Melodic Paralleism between Cui Jian's I have nothing and the Internationale, Barbara Mittler, 2012.

Courtesy:

Private copy, handwritten by Barbara Mittler

Keywords:

Internationale, Cui Jian, I have nothing, Yiwu suoyou, music, rock music, Cultural Revolution

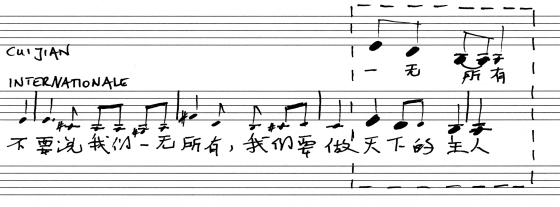

Melodic Paralleism between Cui Jian's I have nothing and the Internationale (Yiwu suoyou, Guojige 一无所有, 国际歌)

Next to the “Internationale,” it was the music of Cui Jian, and especially the songs collected in his 1988 album Rock & Roll on the New Long March (新长征路上的摇滚 Xin changzheng lushang de yaogun) that became something of a “soundtrack” to the Tian’anmen movement (Jones 1994, 150). One song in particular, which was performed at an unofficial concert in a truck on the square only a few hours before the crackdown, quickly became a symbol for the students’ feelings. Its title, “I Have Nothing,” (一无所有 Yiwu suoyou) is a line taken directly from the “Internationale” (Steen 1996, 85). There it is said:

Arise, ye slaves, arise!

Do not say we have nothing,

We shall be the masters of the world!

奴隶们起来,起来!

不要说我们一无所有,

我们要做天下的主人.

Cui Jian’s song was first performed in public in May 1986, and it had been officially praised for its development of a “new Chinese style” in Chinese rock, as in the interludes it employs a suona, next to the regular rock instrumentation. The song is a love song: a young man tries to win over a girl who laughs at him at first because, so he thinks, he “has nothing,” owns nothing—in short, has nothing going for him. When finally, in a last desperate attempt to convince her, he dares take her hand and pull her toward him, he realizes that she loves him dearly, and loves him for the very fact that he “has nothing!”

Is it a love song or a political statement? The young man’s words can be interpreted as the lament of a whole generation, a whole people even, who lost their education, their family, their work, and their faith in socialism (and Mao?) during the chaotic years of the Cultural Revolution and who are thus left with “nothing:” no dreams, no idols, no ideals. Such laments are prevalent in many other forms of art, in so-called wound literature (伤痕文学 shanghan wenxue), wound paintings, poetry, and music. These were not only allowed to exist by the government under Deng Xiaoping, but indeed, officially sanctioned (after initial critical debates). They fit in with the politics of Deng Xiaoping’s “new age” (新时期 xin shiqi) in which many of the Maoist directives from the Cultural Revolution were annihilated or even reversed.

However, the final conclusion of the song is that someone who “has nothing”—no idols, no ideals—is especially loveable. The song thus denies one of the few Maoist directives still in place today, even under the reform policies, namely, the primacy of socialism. If the “Internationale” reads, “Do not say we have nothing, we will be masters of the world,” it expresses optimism, hope—prescribed feelings in the People’ s Republic of China to the present day. However, these feelings are denied in Cui Jian’s song and substituted by resignation and nihilism. That is why, naturally, the song was political. As one critic put it: “China’s youth has socialism! How can they say they have nothing?” (Bai 1988, 94; Steen 1996, 83–86)

This type of political interpretation of a love song has roots in Chinese tradition: in the prefaces to the Book of Songs (诗经 Shijing), China’s oldest collection of lyrics, the compilation of which is traditionally attributed to Confucius, it is declared that poetry is to serve as a ruler’s tool for educating his people and a people’s tool for criticizing their ruler (Riegel 2001). A poem in which a loving wife complains about her husband being far away and having found a new lover can be interpreted, according to this tradition, as the remonstrating voice of a people urging their ruler to abandon his lascivious and wasteful activities and return to the capital to ensure peace and quiet in his country. Even love poetry can carry a potentially political message, then, and whoever writes poetry in China knows of, and makes use of, this exegetical tradition.

But does Cui Jian really criticize, and is his song an attack on the very idea of socialism? Does not his song say, very clearly, that whoever “has nothing” will in the end be loved, and is this belief and the action of finally taking the hand of the beloved and pulling her towards him not exactly the optimism of the “Internationale,” the voice of conviction that slaves will be masters of the world one day? And how, if not optimistically, does one interpret the fact that the falling melodic line sung to “I have nothing” (一无所有 or “o” 噢in the refrain) in Cui Jian’s song is identical to the falling melodic line that, in the original version of the “Internationale,” accords with the words “masters of the world” (天下的主人) as one can see in the illustration?

Does one not have to conclude that, accordingly, those who have nothing are indeed the coming masters of the world? Or is this meant to say, after all, that to be masters of the world is a promise once made but never kept, a promise that leaves all, still, “having nothing?” Is the musical synchronicity linking the two phrases just pure coincidence? Cui Jian has openly stated more than once that rock music is ideology, that it makes political statements. Nevertheless, the message of his song remains enigmatic, and the question as to its ultimate meaning must remain unanswered.