Illustration:

ill. 4.8

Author:

Xu Beihong (1895–1953) 徐悲鸿

Date:

1940

Genre:

painting

Material:

ink and color on paper

Source:

Andrews 1994: Andrews, Julia. Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1979. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994:32, fig.11.

Courtesy:

University of California Press Berkeley

Keywords:

Foolish Old Man, Mao´s writings, Xu Beihong, collective, painting

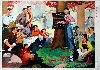

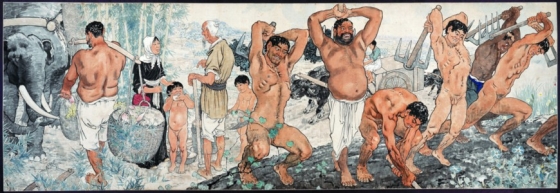

The Foolish Old Man who moved the Mountains (Yu gong yi shan 愚公移山)

In 1940, the painter Xu Beihong 徐悲鸿 (1895–1953) created The Foolish Old Man Who Moved Mountains (愚公移山), a monumental oil painting much admired by Mao. Xu, one of the most famous painters in twentieth-century China, had studied in France and Germany between 1919 and 1927 and had become one of the most important representatives of a synthetic realism and, later, Chinese socialist realism. After breaking with the Nationalists in 1947 because they had attacked him for teaching Chinese art “inadequately,” he almost immediately became an important painter for the Communist movement. When the founding of the People’s Republic was proclaimed on October 1, 1949, Xu was on the balcony at Tian’anmen, just behind Mao (Andrews 1994, 29–32).

Xu’s Foolish Old Man was painted in India, where he was invited by Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) to be a guest lecturer at a local university. Xu’s painting was inspired by the unfaltering spirit of “Saint Gandhi” (1869–1948), as he put it, whom Xu had met through Tagore. Xu finished the painting later in Singapore, where he resided for a time. Some argue that the painting conveys anti-Japanese sentiment, that the Foolish Old Man’s determination also stands for the Chinese people’s determination in their fight against the Japanese. Even if it did contain this message, it was not propagated, for with the official outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War (unofficially, hostilities had been fomenting since 1931), Xu hid the painting in a well at a local school. After the war, in 1949, the painting was given to the school principal as a sign of Xu’s gratitude. It has returned to China only recently.

One element important in later Maoist interpretations of the Foolish Old Man’s story is already visible in this image: this is not really the portrait of an old man, that is, one old man, who moved mountains, but it is the portrait of a collective, a group, hacking away at the rocks. The picture does contain an old man, but with his thin, ascetic (Gandhi-like?) body, he seems rather detached and uninvolved: with his back to the action, he is talking to a woman and child. In this depiction, he appears as more the father of the idea than as the active individual moving the world (and the mountains) himself. The evident strength and the dynamic gestures, obvious in the almost completely unclad muscular bodies of everybody else who is part of the collective, are visual prototypes for later Cultural Revolution depictions of the story.