Illustration:

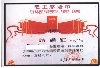

ill. 4.11 a (set: 4.11)

Author:

Barbara Mittler

Genre:

article of daily use, commodity, cushion

Material:

scan, colour, original: linen, embroidery

Source:

Cushion expressing loyalty 忠 to Mao’s Three Old Articles. (Private Copy/Photograph).

Courtesy:

Barbara Mittler

Inscription:

忠,为人民服务, 纪念白求恩, 愚公移山

Keywords:

Lao sanpian, Three Old Articles, Mao´s words, Mao Zedong Thought, everyday life

Cushion expressing loyalty to Maos Lao sanpian

Some years before the Cultural Revolution, in the early 1960s, the story of the Foolish Old Man was propagated as part of a famous trilogy of works known as the Lao sanpian (老三篇, literally “Three Old Articles”) with the significantly skewed but apt official English translation Three Constantly Read Articles. Red Guard publications would A Red Flag article describes why these stories had become popular among workers, soldiers, and peasants, and argues that the people made them into their strongest and sharpest weapon in reforming the world around them. Their views are quoted in a footnote: “We will follow the revolution all our lives, and we will study the Three Articles all our lives” (广大工农兵群众经常地反复地学习这三篇文章, 把它们作为改造主观世界的最强大最锐利的武器, 亲切地把它们简称为老三篇. 他们说: “干一辈子革命, 学一辈子老三篇” HWBZL 1980 Suppl. 1, vol. V, 2324: Xuexi cailiao xuanbian 15 September 1966, 65).

The Three Articles are all based on speeches made by Mao, two of them eulogies. The first of these remembers Canadian doctor Norman Bethune, who served as a doctor in the Chinese army during the Sino-Japanese War and died of blood poisoning because, so the story goes, a Japanese-GMD blockade restricted the supply of protective gloves. In his eulogy, Mao praises Bethune for his internationalism and his altruism.

The second article, entitled “Serve the People” (为人民服务), is the story of Zhang Side, a soldier who died in 1944 while working in a coal-burning stove that collapsed. The circumstances of his death are thus intimately connected with “civil” work, thereby permitting him to appear in three manifestations in later campaigns: as Communist hero, as civilian martyr, and as military martyr, but as a symbol of altruism on top of it all.

Together with the story of the Foolish Old Man, these texts were considered the best vehicle for transmitting the core of Mao’s thought to the masses. They were therefore widely published, increasingly so after the fall of 1966, when Lin Biao once more advocated their study in a speech emphasizing the importance of Mao’s works (CCRD 2002a, Wenge shiqi guaishi guaiyu 1988, 186). During the Cultural Revolution, the Three Articles were sold in mass editions and were indeed “constantly read:” not just during school hours but at any possible moment during the day (Bergman 1984). One middle-school teacher remembers: “Even I could recite by rote Mao’s Three Articles. We had nothing else to read anyway.” (Feng 1991, 88) Many stories illustrate that the Three Articles were well-known even to illiterates. One such story, which relates the experiences of a young intellectual sent to Mongolia in 1967, includes the memorable tale of an old herdsman, Sanggewang, who had learned the Three Articles by heart by having them read aloud (CL 1968.11:53).

Not only taught in schools, the Three Articles were also perused at work and during people’s free time, as the Chinese population was flooded with quotations, emblems, and heroes from the stories. The People’s Daily would print stories and songs based on the Three Articles. There were even vinyl records with recitations for those who could not read (CL 1967.4:137). The stories and their heroes would appear and reappear on posters; in poems and plays; in films, model works, and songs; and on such daily use items as Jingdezhen porcelain, cushions, washing bowls and mirrors, badges, and fingernail clippers as these illustrations show. Accordingly, the three stories and their heroes—the Canadian doctor Norman Bethune, the Communist fighter Zhang Side, and the Foolish Old Man—became household names during the Cultural Revolution (Bergman 1984, 49), “well known to every family, everywhere, in the cities and the countryside” (家喻户晓).