Illustration:

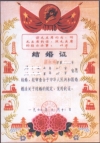

ill. 4.13

Author:

Artist: unknown, Author: Li Lu 作家: 李录

Date:

1989

Genre:

book cover, photograph

Material:

scan, paper, colour

Source:

Li 1990: Li, Lu. Moving the Mountain: From the Cultural Revolution to Tiananmen Square. London: Macmillan, 1990: cover.

Courtesy:

Private copy/photograph by Barbara Mittler

Keywords:

Li Lu, Moving the Mountain, Foolish Old Man, Mao´s words, Tian’anmen Square, Cultural Revolution, heroism, Tankman

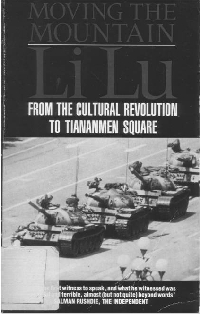

Li Lu: Moving the Mountain

One of the student leaders on Tian’anmen Square in 1989, Li Lu 李录 (1966–), would recall the Old Man’s story and use it as a symbol of hope and strength of willpower among the Chinese. The 1994 film Moving the Mountain (移山), based on Li Lu’s memoir of the same title Moving the Mountain, ends with Li reflecting upon this (Li 1990): "When I think of my life so far through the confusion of images, the image that keeps coming to me is that of an old old Chinese legend that I first heard when I was ten and when the darkness of the Cultural Revolution was just beginning to lift. It was the story of the crazy old man who moved the mountain. [He tells the story and then continues.] Tian’anmen Square is just another attempt to move the mountain. Maybe we failed but we have not given up, and the mountain will be moved." (Li 1994, 78min)

The story of the Foolish Old Man in the film Moving the Mountain comes to stand for the hopes of the Chinese people “when the darkness of the Cultural Revolution was just beginning to lift.” In the film, Mao is not mentioned as the source of the story. This may well be the case because of the primarily Western audience for whom the film was produced. In the book, on the other hand, Li Lu remembers first hearing the story during the Cultural Revolution, when a teacher had told it to him and attributed it to Mao (Li 1990, 40–41). In spite of his knowledge of the source of the story and all that it symbolizes, Li still chose it to be included in his memoirs. Some part of him clearly believes in its Truth. Even in the film version, which denies the story its Maoist heritage, the end of the Cultural Revolution does not put an end to the pathos of Maoist gesture: Li Lu, the heroic leader of the student movement, styles himself into a foolish (young) man.

In his memoirs, Li Lu’s life story is narrated like the making of a (Maoist) hero: the young man rises, is carried by the power of collective energy, and reaches a triumphant end (Lee 1996, 132)—all by believing in the words of Mao (something that remains, naturally, only implicit in the film).

Li Lu’s reinterpretation of the story keeps one important element of Mao’s original speech alive: it uses the story as allegory. It does not give a concrete reading of the story through the life of some exemplary citizen, as do many of the narratives from the Cultural Revolution and early Deng era. Had Li Lu written his story during the Cultural Revolution, the famous tankman shown in the title image of his memoir—or at least, the tankman’s thoughts—would not have remained obscured. We would have known what was running through his mind while he stood up against these tanks: “Be resolute, fear no sacrifice, and surmount every difficulty to win victory.” And it would have been to the sound of these words that numerous students and workers would have faced the machine guns of the PLA, too, although they would not have stayed invulnerable after all. Yet, Li Lu does not choose this type of narrative; he nowhere explains the story and its importance in a concrete manner, and thus by staying in the abstract, he returns to and retrieves something of its original (Yan’an) aura.