ill. 4.1, metadata

ill. 4.1, metadata

ill. 4.2, metadata

ill. 4.2, metadata

ill. 4.3, metadata

ill. 4.3, metadata

ill. 4.4, metadata

ill. 4.4, metadata

ill. 4.5, metadata

ill. 4.5, metadata

ill. 4.6, metadata

ill. 4.6, metadata

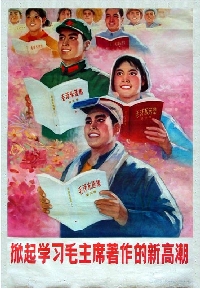

The Power of Mao's Words

This propaganda poster published in 1977 and entitled Let’s set off a new upsurge in the Study of Mao’s works 掀起学习毛主席著作的新高潮 shows a group of people suspended in a sea of pinkish flowers, three in front (worker, peasant and soldier) and a group of 7 (men and women from different walks of life and ages) further in the back, each of them holding the newly published 5th volume of Mao’s works in their hands. They all look up, with a happy smile, into the bright future that this clearly promises them: all of the books are opened which suggests that each of them has just been reading them. Mao’s works are the focal point of the image. This is achieved not by positioning them in central position but by presenting them in repetition: the book, in the typical simple red and white covers, is held in many a pair of strong and handsome hands who inspire confidence and faith in the future of a country relying on the words of Mao.

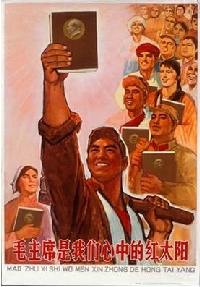

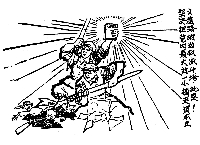

Propaganda posters from the Cultural Revolution such as this one of 1966 (ill. 4.2), entitled Mao is the Red Sun in our Heart 毛是我们心中的红太阳 show a worker hero is in the centre, holding up a copy of Mao’s works, a brownish book, ornamented with Mao’s standard profile portrait, exuding (pink) rays like a sun. The worker is flanked by a female peasant and a male soldier, while a very heterogenous group from all walks of life (and nationalities) is seen in the background, each of them holding the identical book of Mao’s writings ornamented with Mao’s portrait close to their heart. Depictions such as these, in which Mao’s works are dramatically put into scene by means of elevation, repetition and accentuation, appeared both before (ill. 3.9) and after (ill. 4.1), but especially during the Cultural Revolution. Red Guard Publications include numerous woodprint illustrations praising the might of Mao’s Thoughts in fighting so-called “capitalist roaders” in the Party such as Chen Yi 陈毅 and Liu Shaoqi 刘少奇 (ill. 4.3).

Mao’s writings are pivotal, the central focus in these images. Here, a book of his writings is held up in the hand of a female revolutionary with a sword in hand. The book emanates rays like a sun which enclose the two young revolutionaries who stand erect, fighting with two minute figures, one of which is identified as Liu Shaoqi: he is holding up a piece of paper with 修养 “self-cultivation” written on it, the Confucian virtue advocated by Liu in his book on how become a “good Communist” (Liu 1965). In many of these images, as we have seen, Mao’s writings are visually translated into a sun, that is, Mao himself, the “red sun in everyone’s heart,” is symbolically understood to give strength to everyone to fulfill further heroic deeds.

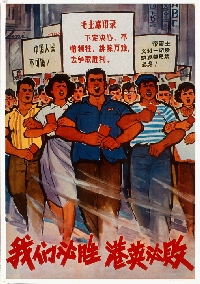

Mao’s Thoughts acquire another materiality in the 1967 poster, printed in connection with the Hong Kong Riots raging between spring and winter of 1967 (ill. 4.4). During the riots, attempts had been made by Communist forces to “win back Hong Kong” by manipulating strikes and demonstrations, causing a lot of violence. The riots were unsuccessful and subsided by the end of the year. Entitled We will be victorious and the English in Hong Kong will lose out 我们必胜港英必败, it shows a group of strong and youthful demonstrators, men and women alike, with typically huge forearms, moving swiftly forward (their strength and vitality supported by the speed lines in the foreground of the picture). Each of them is holding a Little Red Book of Mao quotations, and some of the demonstrators are raising, in addition, posters with Mao quotations, most of them taken from the Little Red Book: “The Chinese people will not be humiliated” says one, “Imperialism and all reactionaries are paper tigers,” the next (this being the title of chapter 6 in the Little Red Book) and “Be resolute, fear no sacrifice and surmount every difficulty to win victory,” (from chapter 19 in the Little Red Book) a third. Again, it is repetition, here occuring on different levels and in different materialities, which serves to emphasize the importance of Mao and his words.

The next image (ill. 4.5) from the cartoon Children of the Grasslands 草原儿女 Caoyuan ernü (which later also became a model ballet) appears in 1973. It shows a father explaining to his children that they must be diligent and learn from Chairman Mao. They are kneeling in front of a large Mao portrait, each of them (and their father) holding a book with Mao’s writings in their hands, and many more such books are waiting on the table.

The power of Mao’s words thus learned are, so these images suggest, appreciated by everyone. The impossible becomes possible by remembering Mao famous quote: one of the little sisters (Comic Caoyuan Ernü 1973:63) remembers Mao’s phrase of being resolute enough to “overcome difficulties” when at one point later in the story, where she and her sister are lost in a snowstorm, she has almost given up fighting the snow. As she mumbles Mao’s words to herself, she remains determined not to let go and soon enough, the snowstorm dies down (Comic Caoyuan Ernü 1973:64). Her determination (based on her earlier diligent reading and memorizing of Mao’s works with her father) has saved her. What these different depictions insinuate, then, is that Mao and his writings (and not just the Sanzijing discussed in the last chapter) are indeed, as one four-word phrase has it, “well known to every family, everywhere, in the cities and the countryside” 家喻户晓.

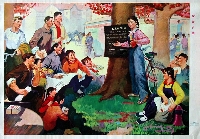

The last propaganda poster in this set (ill. 4.6), published in 1975 even bears this as ist very title. It shows a young girl who has hung upon a tree in the centre of the image a blackboard with a quotation by Mao. People from all walks of life gather around the blackboard, some more seriously (like the old woman sitting in the foreground) others more casually (like the young man in the back, who is just arriving on his bicycle). Almost all of them are holding different paraphernalia related to reading and studying Mao: newspapers, booklets, notebooks. The backdrop, too, to the scene, which shows more people reading and posting big-character-posters at some of the surrounding (house-)walls, emphasizes this intense atmosphere of ideological instruction and learning. Numerous images of this sort could have been seen during the Cultural Revolution (cf. ill. II.1, ill. II.2, ill. 1.10).