Illustration:

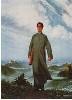

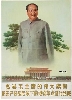

ill. 5.24

Author:

Yu Youhan (1943-) 余友涵

Date:

1989

Genre:

oil painting

Material:

scan, paper, colour; original source: oil on canvas, 89 cm × 121 cm, colour

Source:

China Avant-Garde, edited by Jochen Noth et al., Heidelberg: Brausdruck, 1994; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995:182., Heidelberg catalogue entry

HeidICON Image ID:

86098

Keywords:

Tian’anmen Square, popular culture, Pop art, 'Westernization', 'bright, shining, red', Mao portrait, Mao´s portrait, twenty-first century, China Avant-Garde

Yu Youhan: Mao Zedong on The Stage At Tiananmen Square (Yu Youhan: Mao Zedong zai Tiananmen chenglou shang 余友涵: 毛泽东在天安门城楼上)

Some of the Mao portraits created since the 1980s and into the 1990s may illustrate the fact that the implied audience of MaoArt after the end of the Cultural Revolution is no longer as clearcut as it once was (see ill 5.24, ill. 5.25 a, ill. 5.26, ill. 5.27 a): they purposely play with the idealized, perfect form and figure of Mao portraiture from the Cultural Revolution by citing it. Yet, the message which their quote conveys has changed, clearly.

It is obviously not the form but the colour and technique which would have made the flower-patterned, deliberate double-misprint citation of an official portrait of Mao at Tian’anmen 泽东在天安门城楼上, painted in oil by Yu Youhan 余友涵 (1943-) in 1989 unacceptable by Cultural Revolution standards. As during the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s image is obviously aestheticized here. With its open colours, light blue and army green (good colours in traditional operatic terms, as will be remembered), it could even be considered “bright and shining”—if not “red.”

Much unlike depictions proliferating during the Cultural Revolution, however, this portrait introduces an aesthetics not of Chinese revolutionary but of commercial, of “capitalist” popular culture, and PopArt (probably reflecting the 1985 Rauschenberg exhibition in Beijing). Mao’s face is not entirely focussed due to the deliberate misprinting of the flower pattern and his features are white, including a white “advertising smile.” It is this hyperbole, in combination with the fuzziness, created by the multiple print, which somehow points to the farcical quality of political propaganda (DalLago 1999:51).

On the other hand, it also plays with the obvious similarities between propaganda (i.e. the use of techniques of Socialist Realism—or Revolutionary Realism and Revolutionary Romanticism as it would be called in China—which Yu Youhan unmasks, elsewhere in his oeuvre as “Westernization”) and commercial art, as well as ridiculing them at the same time. The implied audience for a picture such as this has fallen precisely for the appeal of this—now unmasked—aesthetic double bind which Yu repeatedly dissects in his paintings. (See also DACHS Continuous Revolution).