Illustration:

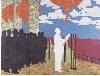

ill. 5.27 d (set: 5.27)

Author:

Wang Xingwei (1969 -) 王兴伟

Date:

1994

Genre:

oil painting

Material:

scan, paper, colour; original source: oil on canvas 240 x 300 cm

Source:

Wang Xingwei, Dawn, 1994 (DACHS 2009 Wang Xingwei Going to Anyuan), Heidelberg catalogue entry

Courtesy:

Wang Xingwei, Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne

Keywords:

sunrise, sun, Red is the East, revolutionary gestures, stride forward, turn backward, hero, Mao Zedong

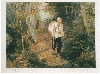

Wang Xingwei: Dawn (Wang Xingwei: Shuguang 王兴伟: 曙光)

In another image from the set, entitled Dawn 曙光 1994 (ill. 5.27d), we see the young man together with a young lady, obviously in a romantic set-up, she seated, he standing up, again, with his back to the viewer, pointing forward, in a “revolutionary” gesture, once more, toward a point far, far away, on the horizon where, again, the sun is rising.

There are quite a few repetitions or echoes between the images: each of them is quoting and mixing different visual traditions and languages, but the intervisual echoes are not easy to read: Why Hitler and Mao? Why the repeated references to the sun and thus, Mao? Why the revolutionary gestures, the fists, the strides forward (and turns backward), in inappropriate settings? Why is the hero (an “angry young man”?) almost always turning his back to the viewer, his conversation with Hitler being the exception? Is this a response to, and an open denial of the open portraiture of heroes that the painter has grown up with? Where will the finger pointing into the far distance lead Hitler or the loving couple? What happens to the blind man with his forceful strides? And to Hitler and the burning object? Will the sun (Mao, still?) protect them or simply shine on their useless deaths? Is there hope? Is Mao introduced as an alternative to Hitler or compared to him? Or must one turn one’s back on Mao, as the Anyuan parody suggests, in order to go global and move into a brighter future after all?

According to the artist, satirical play with well-known visual material was the most important aim behind all of his creations in these years and indeed, the hilarity of the rather unusual cases of mistaken identity which he creates in these images, reflecting on and echoing each other, is rather irresistible (cf. DalLago 1999:52). In the Anyuan parody (cf. ill. 5.1), Mao is cited ex negativo: he is there as a silhouette formed by way of the familiar background. But what does it mean that in the Anyuan parody Wang/Mao has taken the fatal decision to turn away from Anyuan?