Illustration:

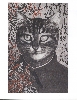

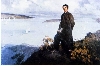

ill. 5.28

Author:

Wang Xingwei (1969 -) 王兴伟

Date:

2000

Genre:

oil painting

Material:

scan, paper, colour; original source: acrylic on canvas, 220 x 165 cm

Source:

Wang Xingwei, X-Ray, 2000 (DACHS 2009 Wang Xingwei Going to Anyuan), Heidelberg catalogue entry

Courtesy:

Wang Xingwei, Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne

Keywords:

parody, Mao goes to Anyuan, young Mao, old Mao, Maoist past, mountains, clouds, Mao Zedong

Wang Xingwei: X-Ray on Mao goes to Anyuan

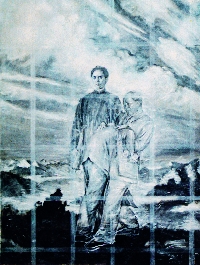

Wang Xingwei returns to his Anyuan parodies with this image, entitled X-Ray (2000). It uses the Anyuan picture uncovering, according to the artist, its several “psychic layers.” The original Anyuan image is reproduced in grey tones here, a grid pattern is applied over it. The grid pattern surfaces two more older Maos in the picture, right in front of the young Mao, one convulsively covering his head and face, turning back, ducking down, trying to hide behind the young Mao’s back, the other attempting to move forward forcefully, with his foot astride, somehow attempting to push the crouching Mao back again.

Does this image reflect on the history of the Anyuan story? Or does it play with the young man’s turn in the Eastern Way series? Is it suggesting that Mao, too, in his later days, had his scruples about his own position? That he, in fact, thought about turning back, too, like so many around him? And what does this mean for those living with Mao’s heritage? Is it a way of coping with some of the more traumatic experiences associated with the Mao era to be able to say that he turned his back on these policies, too? What does this series of images say about the Maoist past and its legacy? Do they turn their backs or show new ways? And how dangerous are they? These are the kinds of questions that these images pose but somehow do not answer.

In an act of artistic self-referentiality, the grid points to how Mao, the much-repeated icon, would come into being, how he was in fact (mechanically) reproduced so many times: already in traditional China, grids had been used for copying paintings. This technique was also employed for Mao portraits. The grid distances not just the viewer, but the painter, too, from his object: it serves as a gauge, it provides an analytical framework, and thus it may work to liberate the artist engaging with the image from subjective expectations and emotions. Representation itself, as indicated by this hint towards its mechanical engendering, in addition to the serial repetition through which the portrait is presented, becomes a schema, a formula insinuating the semantic emptiness of the sign, Mao itself. (Köppel-Yang 2003:159, Wu 2005:185)