Illustration:

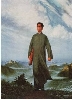

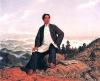

ill. 5.30 a (set: 5.30)

Author:

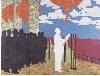

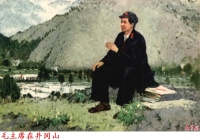

Luo Gongliu (1916-2004) 罗工柳

Date:

1961 / 1962

Genre:

oil painting

Material:

scan, paper, colour; original source: oil painting

Source:

Luo Gongliu, Comrade Mao Zedong at Mount Jinggang, 1961/62, (DACHS 2009 New New Year Prints).

Keywords:

Mao Zedong, Mao portrait, Autumn Uprising, young Mao, mountains, clouds, Chinese landscape painting

Luo Lingguo: Comrade Mao Zedong at Mount Jinggang (Luo Lingguo: Mao Zedong tongzhi zai Jinggang shan 毛泽东同志在井冈山)

This oil painting by Luo Gongliu 罗工柳 (1916-2004) of 1961/62 shows a pensive Comrade Mao Zedong at Mount Jinggang 毛泽东同志在井冈山 to where he turned after the failed Autumn Uprising, awaiting the arrival of troupes under Zhu De and Chen Yi to join his forces. The young Mao is the central figure of this image, his strong and sturdy body is marked through dark clothing which contrasts sharply with the grey-and-white background. The only real colour in this picture is the red star on his Mao Cap and the red patches at the collar ends of his jacket, echoed several times in a few rather blurred reddish patches in the landscape. Mao’s greatness is, according to traditional painterly principles, echoed in the greatness of nature: the rolling mountain peaks (above and behind him, they look as if lifted from a classical Chinese painting), and the vastness of the rice paddies in front of which he sits, leisurely, on a rock, a pile of papers next to him, taking a short rest from studying, smoking. His eyes are directed straight and slightly upwards toward the left: he appears to look into the future.

This image has been praised for being a successful experiment in the sinicization of oil painting. Luo uses the longer, curved strokes from Chinese painting, not the large and squared brush strokes used in the Russian painting tradition also taught in China, and employs regular vertical dabs to suggest foliage, a technique taken from Chinese landscape painting. To the uneducated eye, the image may appear reminiscent of European pointillist traditions, too, which does make sense since Luo was trained under Lin Fengmian and his francophile faculty at the National Hangzhou Arts Academy (Andrews 1994:245-246).

Why is it that an image such as this one did not make it into the ranges of the propaganda posters or national exhibitions although Luo Gongliu had been one of the most respected artists in charge of attaining art work for the Central Museum of Revolutionary History in the 1950s and for the ten year anniversary of the foundation of the People’s Republic of China (Andrews 1998:228-229)?

Both in terms of colour and style, this piece can be considered unacceptable within the Cultural Revolution pantheon of correct artistic expression. The cool colours dominating the picture are out of the ordinary in Cultural Revolution style. Moreover, the faintly pointillistic, modernist brushwork, too, even if it can be explained with a reference to Chinese tradition as well (it is the “aristocratic” tradition of ink painting, after all) is not appreciated during the Cultural Revolution.