Illustration:

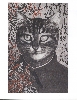

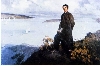

ill. 5.32 a (set: 5.32)

Author:

Li Qi (1928-) 李琦

Date:

1958

Genre:

painting

Material:

scan, paper, grayscale; original source: ink and colour on paper, 74 x 56 cm

Source:

Andrews 1994: Andrews, Julia. Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1979. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994:212.

Courtesy:

University of California Press Berkeley

Inscription:

同铲一筐土 共用一条巾 敬爱毛主席 和咱心连心

Keywords:

guohua style (国画, national style), workers, industrial labor, Chinese landscape painting style, Mao portrait

Li Qi: Mao at the Ming Tombs Reservoir (Li Qi: Zai shisan Lingshui ku gongdi shang 李琦: 在十三陵水库工地上)

During the first half of the Cultural Revolution, one sees no newly publicized compositions of MaoArt in a style comparable to that of Li Qi’s 李琦 (1928-) 1958 painting Mao at the Ming Tombs Reservoir 在十三陵水库工地上 as seen here (ill. 5.32a), or his oft-quoted 1960 image of Mao with the straw hat, with the significant title, The Chairman goes Everywhere 主席走遍全国 which is the next image (ill. 5.32b).

Both paintings are in so-called guohua style 国画 (national style), retaining the loosely-brushed qualities of traditional painting, the first to be seen here even inclusive of a four-word archaizing poem—praising how under Mao’s rule “all hearts (are) united” 心连心. In these paintings, traditional techniques are used for the depiction of contemporary social settings. In Mao at the Ming Tombs Reservoir, for example, industrial labour is depicted and mighty cranes substitute for dainty trees before an albeit very typically depicted Chinese-style landscape. The image shows Mao’s ritualistic emergence into labour in May 1958, with shovel in hand, a worker offering him a sweat towel and other workers standing by, watching the scene happily. Many images like these have been produced in the 20th century. Here, Mao is the central focus, his position is slightly elevated with regard to all other protagonists. Accordingly, in terms of structural composition, there would have been no trouble for this picture during the Cultural Revolution, yet oral history suggests that Li Qi’s 1960 picture of Mao with a straw hat, to be seen next, remained a visual presence throughout the Cultural Revolution decade (ill. 5.32b).

Li Qi himself, did not fare so well: not only had he painted portraits of Liu Shaoqi which became dangerous for any Chinese artist in the early years of the Cultural Revolution (Andrews 1994: 328), but the very “aristocratic” style of “national-style” painting which he employed, painting with traditional Chinese pigments on traditional Chinese paper, was, at least officially, condemned during the early years of the Cultural Revolution (Hawks 2003).