Illustration:

ill. 5.41

Author:

Wang Guangyi (1957-) 王广义

Date:

1988

Genre:

oil painting, triptych

Material:

scan, paper, grayscale; original source: oil on canvas, triptych, each 150 x 120 cm

Source:

Köppel-Yang 2003: Köppel-Yang, Martina. Semiotic Warfare: The Chinese Avant-Garde, 1979-1989. A Semiotic Analysis. Hong Kong: Timezone 8, 2003:152, fig 68.

Courtesy:

Martina Köppel-Yang

HeidICON Image ID:

198059

Keywords:

Mao Zedong, Chinese avant-garde, Mao Cult, Mao Fever (1980s), Mao portrait, rational painting, 理性绘画, Mao memories

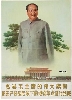

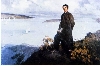

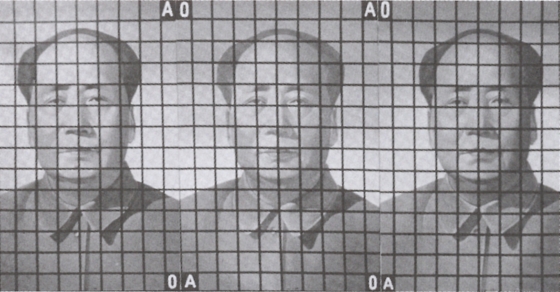

Wang Guangyi: Mao Zedong Black Grid (Mao Zedong hei ge 毛泽东黑格)

Wang Guangyi 王广义 (1957-), in his triptych Mao Zedong Black Grid 毛泽东黑格 composed in 1988 and exhibited at the fateful China/Avantgarde exhibition in Beijing in 1989, visually operates in a very similar manner to Ai Weiwei (ill. 5.40), but understands his image as a critical answer precisely not to fading memories of Mao but to the rising Mao Fever 毛热 of the late 1980s. His image, which references Mao’s standard portrait, repeating it three times in grey tones, and putting it behind a grid, as if Mao were in a jail, looking out of the barred window (or, otherwise, as if someone was looking from the jail toward a “visiting” Mao) is considered “one of the most controversial and renowned works of Chinese avant-garde art from the 1980s” (Köppel-Yang 2003:152).

Recognizing its importance, the convenors of the 1989 China/Avantgarde exhibition had it displayed in the center of the exhibition space on the first floor of the National Gallery. The reactions both of the public and of the government to the image show its ambiguities: each corner of the grid has a letter attached, either an A or an O. The letters were misread by some as A and Q: Mao behind the grid was thus connected with a fictional figure by Lu Xun, the Chinese everyman AhQ, a stubborn and stupid fellow whom Lu Xun had created in the 1920s to criticize the Chinese mind and prompt reform and revolution. Wang Guangyi immediately disclaimed this connection by painting over the Os and making them into Cs, thus stressing the arbitrariness of the choice of letters. It remains unclear whether the letters are or were supposed to mean anything.

To the Christian viewer, who already reads meaning into the triptych form, these letters immediately point to alpha and omega, and the remark made by God in Revelation 1, 21 and 22, “Ego sum alpha et omega” (I am the beginning and the end) which would have opened up a discussion about how necessary Mao was and is as a “spiritual being” for China’s existence and which would thus be a direct response to the question of Mao’s “fading nature” addressed by Ai Weiwei’s triptych. This interpretation would also tally with the artist’s own vision of the image. He considers it a work of rational painting 理性绘画: he uses colours with cold expressive qualities, conveying (e)motionlessness and thus, critical distance and objectivitation, silence, and coldness. The Grid, too, serves as a means of distancing the viewer from the viewed. Mao, the image—if considered from a distance—is demystified.

The triptych thus presents a critical view not so much of Mao as a historical figure, but as the object of (irrational?) religious worship, a form of representation which had dominated Chinese visions of their political leader since the founding of the People’s Republic of China but had peaked during the Cultural Revolution and, after a short (superimposed) lull in the early 1980s, found a popular revival in the late 1980s (Köppel-Yang 2003: 157-158).