Illustration:

ill. 5.47

Date:

1994, November / December

Genre:

calendar, photocollage

Material:

scan, paper, colour; original source: photocollage

Source:

Barmé 1996: Barmé, Geremie R. Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1996:99, fig. 30 c.

Courtesy:

Geremie Barmé

Keywords:

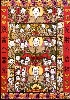

Mao Zedong, Mao portrait, repitition, Mao memories, Maoist past, clouds, children, red bandanas, masses

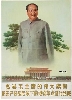

Image from 'Remember Mao Zedong and Be Grateful to Deng Xiaoping'

The changing but everpresent value of the Maoist past in China’s present is not just reflected in Political Pop (Li 1993), the first form of contemporary Chinese art which, often misunderstood (as plainly obvious in Yu Youhan’s case) as “dissident art,” was hugely successful outside of China (cf. DalLago 1999, Wu 2005:203-204 and forthcoming work by Tang Xiaobing). Repetitions of Mao sell, on a more popular level, not only in the West, but in China, too: this 1994 calendar, for example, presents multiple visions of multiple Maos.

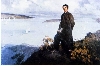

One page shows Mao, sitting to the right, in a position very similar to that in Luo Gongliu’s depiction of Mao at Jinggangshan (ill. 5.30), facing a photocollage billboard featuring images of himself in different stages of his life, hanging from a sky with majestic (and, as we have seen, since Liu Chunhua’s Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan, significant) clouds. Mao sitting on the bench is looking at this billboard of his pasts intently, while another Mao is walking towards him, serenely and leisurely.

The message of this image is further complicated by the fact that it is accompanied by a commentary in which the concluding verses from a 1954 poem (北戴河—written at the seaside resort Beidaihe) in which Mao reflects on thousands of years of Chinese history, is cited: “Today the autumn wind still sighs. But the world has changed!” 萧瑟秋风今又是, 换了人间. The commentary refers further to two of the more famous photographs of Mao contained in the collage, one with children sporting red bandanas, the other of Mao in a crowd of smiling visitors from the Third World. It reads: “A youth tied a red bandana around his neck; people of different races smiled in his presence. He, however, deeply questioned all of this: ‘How many of them are true believers?’ He was no different from anyone else; he didn’t enjoy seeing the masses all wearing the same expression.” (Barmé 1996:99)

The message to be constructed from this picture is polyphonic, to say the least. Did Mao—who is seen sitting there, reflecting on his past (as he did on Jinggangshan, most catchingly depicted by Luo Gongliu, ill. 5.30a)—really doubt the faith of his followers when he saw them through precisely the images that had once constituted pervasive everpresent propaganda? Is he aware that only he could make them “wear the same expression” all the time? And if the world had changed so much, why was he, Mao, still there, on the pages of a calendar produced in the mid 1990s and sold at a good price? Is Mao just as long-lived as the autumn wind, then? Images like this must perhaps remain enigmatic in the final analysis, but they are, once more, reflections on and different answers to Mao’s omnipresence in China’s past as well as in her present.