Illustration:

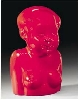

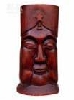

ill. 5.74

Author:

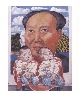

Wang Keping (1949-) 王克平

Date:

1978 / 1979

Genre:

sculpture

Material:

scan, paper, colour; original source: wooden sculpture, height: 67 cm

Source:

Andrews 1994: Andrews, Julia. Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1979. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Courtesy:

Wang Keping, Zürcher Paris, NY.

Keywords:

Mao Zedong, God, parody, Chinese avantgarde, idol, red star, Mao memories, Mao Cult, Buddha, icon, iconography, leader

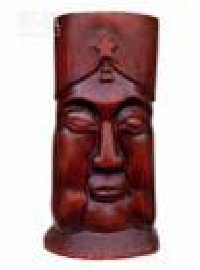

Wang Keping: Idol (Wang Keping: Ouxiang 王克平: 偶像)

Mao as a godlike figure also finds more ironic reflections. Wang Keping’s 王克平 (1949–) 1978–79 statue Idol (偶像) is one such example. Wang was a member of the so-called “Stars” (星星) group of painters, made up of former Red Guards. Their name is a naughty reference to a 1930 article by Mao, frequently quoted during the Cultural Revolution, in which he wrote, “A tiny spark [i.e., the stars] can start a prairie fire” (星星之火可以燎原) (Mao 1952). Wang’s Mao statue is a typical example of the strongly political tone of the group’s artistic activities. As part of the Stars’ outdoor exhibition in 1980, Idol visualizes the leader’s godlike status, overlapping Mao’s features with those of an ironically winking corpulent Buddha in late Tang or Song dynasty style (DalLago 1999, 51).

By choosing such a conspicuous name, the sculpture plays with Communist criticism of religious superstition by unmasking Mao, the Communist icon, as just one such object of superstitious worship. When Michael Sullivan visited Wang, he observed that Wang had even moved an abject kneeling figure in his atelier to face the idol in order to drive his point home (Sullivan 1996, 166). Yet, whether the statue indeed must be seen as a caricature of Mao has been questioned. Martina Köppel-Yang argues the opposite but says that the work’s significance lies precisely in this “collective misunderstanding,” the general consent that defines it as a Mao parody (2003, 120–30).

Her analysis of this “collective misunderstanding” illustrates the importance of Mao as visual propageme (Gries 2005, 13–34). The audience’s immediate association of the figure with Mao reveals the efficiency of Chinese political propaganda. Mao’s image has been repeated so many times that he has indeed become an integral part of everyday life; its repertory of signs has infiltrated people’s collective unconscious. The audience association of this sculpture with Mao also indicates the very sensibility with which Chinese people react to propaganda. By juxtaposing discordant elements—the physiognomy of a Buddha connotes dignity, while the facial expression suggests a comic mood, the Communist star and the traditional dignitary’s hat do not tally with each other—the ensemble appears quite absurd. The work thus demonstrates the vanity of the object of the cult, thus questioning the significance of idols as such. Confronted with an ambivalence of signs, the viewer is also made aware of the mechanisms of propaganda, which integrates signs from different and contradictory domains. Wang thus criticizes the fanatic collective idol worship and propaganda (the aestheticization of politics) of the Cultural Revolution—super-idol Mao foremost among them—as the direct opposite of autonomous action. At the same time, he calls for the emancipation of the individual whose fundamental right it is to doubt authority (Köppel-Yang 2003, 124).