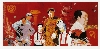

Illustration:

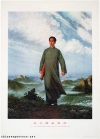

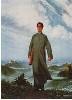

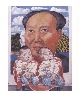

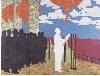

ill. 5.82

Author:

Li Shan (1942-) 李山

Date:

1994

Genre:

art original, painting

Material:

internet file, colour; original source. framed, acrylic on canvas, 148 by 179 cm, colour

Source:

DalLago 1999: DalLago, Francesca. “Personal Mao: Reshaping An Icon in Contemporary Chinese Art—Chinese Political and Cultural Leader Mao Zedong.” Art Journal 58, no. 2 (1999): 47-59.

Courtesy:

Li Shan

Keywords:

Mao Zedong, Mao portrait, Chinese avantgarde, Mao Cult, nostalgia, icon, iconography, hero, Mao memories, flower, Mao cap, red star, Mao Suit, political pop, Pop art

Li Shan: Mao with the Artist

Even some of the controversial pieces by the Chinese avant-garde since the late 1980s and early 1990s can be interpreted as products of an obsession with Mao: just like the Mao Cult, these images according to art critic and curator Li Xianting 李宪庭 (1949–), are the sign of a fixation “that still haunted the popular psyche,” combining “both a nostalgia for the simpler, less corrupt, and more self-assured period of Mao’s rule with a desire to appropriate Mao Zedong, the paramount god of the past, in ventures satirizing life and politics in contemporary China.” (Barmé 1996, 216)

Accordingly, for a painter to spend the better part of a decade painting Mao and only Mao almost exclusively was not the exception but rather the rule. Perhaps the most radical example is Li Shan 李山 (1942–), whose work is primarily based on Mao who becomes a figure both of projection and of annihilation of the artist’s self. Francesca dalLago analyzes Li’s painting Mao and the Artist (1994) as follows: "Here, Mao and Li coquettishly lean on each other, holding in their hands two sensually stylized flowers. Their facial traits demonstrate an effect of mutual assimilation, in which the older Mao is portrayed as a semiclone of the artist. The political icon is progressively absorbed within the artist’s persona and rendered as the projection of his psychological journey during a decisive moment of his own history. By feminizing the traits of a desirable hero—and investing the icon that so profoundly marked the horizon of a whole generation with the signs of his own desire, Li attempts to rescue his individual self from “the pillaging that was history.” And yet his portrait still maintains a degree of inaccessibility that locates it on a different level from that of the viewer. The iconic properties derived from the original version are preserved in the reworked format, endowing it with a puzzling aloofness. This resistance to a single mode of readings endows the “new” Mao with an undefinable quality that becomes a significant form of expression for a country traversing a period of intense moral and material changes." (1999, 58)