Wang Xingwei parodies on Mao goes to Anyuan

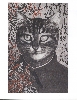

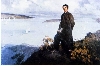

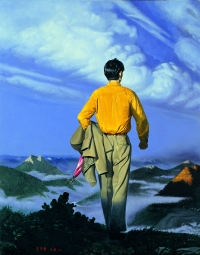

Self-reflection turned into reflections about Mao and his importance to the reflecting self is the topic of Wang Xingwei’s 王兴伟 (1969-) painting 东方之路 The Eastern/Oriental Way from 1995 as well. It shows a sleek businessman on a “Journey South” 南巡—which Deng Xiaoping had taken just a few years before the painting was conceived, in 1992, to support more expansionist economic policies. The young man, a double of the artist, who recurs in a number of enigmatic paintings from the same year, appears here in Mao’s stead: dressed in shiny ocre suit and tacky yellow shirt, he is added to a background which is a rather accurate copy of Liu Chunhua’s famous model painting Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan.

The image thus cites a paradigmatic vision of Mao without showing Mao: the clouds above the young man in yellow and the majestic mountainscape at his feet are exactly the same as in the original. The young man who has been cast in Mao’s position holds, characteristically, the peculiar (here pinkish) umbrella in his hands (which, if read in conjunction with another image from this series, appears to be made of pink plastic, however, no longer of paper as in the hands of the “original” Mao portrait, see ill. 5.27 c). Yet this young man has turned away from Anyuan, he walks the other way, perhaps he even decides to “go global” 走出去, a policy which drew on the experiences of Deng’s Southern Tour, had been practiced since the mid-1990s to be officially implemented in 1999 (Jungbluth 2011). Here, as in the other pictures of the series, Wang establishes visual parallels with well-known artistic themes, materials and gestures and thus creates, especially through the many subtle interconnections within the series, a rather complex set of associations.

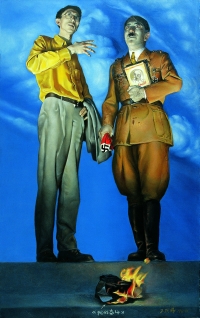

Arguably the most enigmatic image of the series shows the same young man together with Hitler (ill. 5.27 b) in a low-angle shot, a technique often used in scenes of confrontation to illustrate which character holds the higher position of power and thus an important aesthetic gesture in, for example film noir—but also in Cultural Revolution model works. It is clearly the young man who is the one in power. While he, too, is seen from below, he appears much taller than Hitler. And apparently, he is explaining to him, who, in turn, is nervously clinging to his book, Mein Kampf, holding it tight, his hand forming a strong fist, the need to make peace, not war. The 1996 picture’s title is Mein Kampf—Wang Xingwei in 1936 我的奋斗—王兴伟在 1936. The background is the inevitable cloudy blue sky, both Hitler and the young man are looking up to this sky, a vision clearly before them: in Soviet protocol, to marvel at an immense sky or expansive view is a sign of the subject’s confidence in the coming of the Communist utopia, part of the reason why Stalin in his official portrait (and Mao in his based on Stalin’s) has this fixed gaze into the sky (Hawks 2003:297). Wang and Hitler are transfixed by Wang’s vision, and thus, they are not looking at the object (what is it?) which is lying, in flames, on the staircase right in front of them. What will happen? Here, as in many of the other images in this series, the characters are depicted as on a threshold (here, at the top of the stairs), below the open skies. All of them, so this visual device seems to suggest, are about to make a fatal move.

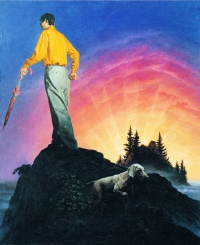

In two other images of the series, the young man is seen, as in the Anyuan parody, on the top of a mountain ridge. One is in a seemingly hopeless situation, a dead end at the peak of the mountain, with a dog already turning back onto the one and only path down the hill where they have come up (ill. 5.27 c, Blind 盲 1996). The young man, on the other hand, with his hands in determined fists and his (plastic) umbrella pointing forward, is marching on, going forward (into the air and thus, his death?). He is blind, as the title of the painting suggests, and this fact, in combination with Maoist rhetoric where “going forward” 往前进 is always considered the one and only direction one would and should take, makes for a very ambiguous message. This is even more true as an extremely kitschy sunrise (never innocent in China, to be sure, since that famous song “Red is The East”) is seen in the background. What would be the purpose of this young man’s going forward into his death? His would not be a heroic act but one of sheer waste. Does this throw a light on some of the other deaths caused by forcefully “going forward,” blindly (if not blindfolded in red, as with Cui Jian and Zhu Wei, in ill. 5.26, but the message appears to be the same) and blinded?

In another image from the set, entitled Dawn 曙光 1994 (ill. 5.27 d), we see the young man together with a young lady, obviously in a romantic set-up, she seated, he standing up, again, with his back to the viewer, pointing forward, in a “revolutionary” gesture, once more, toward a point far, far away, on the horizon where, again, the sun is rising. There are quite a few repetitions or echoes between the images: each of them is quoting and mixing different visual traditions and languages, but the intervisual echoes are not easy to read: Why Hitler and Mao? Why the repeated references to the sun and thus, Mao? Why the revolutionary gestures, the fists, the strides forward (and turns backward), in inappropriate settings? Why is the hero (an “angry young man”?) almost always turning his back to the viewer, his conversation with Hitler being the exception? Is this a response to, and an open denial of the open portraiture of heroes that the painter has grown up with? Where will the finger pointing into the far distance lead Hitler or the loving couple? What happens to the blind man with his forceful strides? And to Hitler and the burning object? Will the sun (Mao, still?) protect them or simply shine on their useless deaths? Is there hope? Is Mao introduced as an alternative to Hitler or compared to him? Or must one turn one’s back on Mao, as the Anyuan parody suggests, in order to go global and move into a brighter future after all?

According to the artist, satirical play with well-known visual material was the most important aim behind all of his creations in these years and indeed, the hilarity of the rather unusual cases of mistaken identity which he creates in these images, reflecting on and echoing each other, is rather irresistible (cf. DalLago 1999:52). In the Anyuan parody, Mao is cited ex negativo: he is there as a silhouette formed by way of the familiar background. But what does it mean that in the Anyuan parody Wang/Mao has taken the fatal decision to turn away from Anyuan?