MaoArt

An attempt at emptying and distancing Mao is at the heart of Zhang Hongtu’s project conducted between 1991-1995 and entitled Material Mao (ill. 5.42). He empties out Mao, makes him fade and disappear not by showing a scratched or blotted-out surface, not by putting a visible grid over his image, but by not even operating with a painted outline. He presents a long series of Mao-Silhouettes, i.e. cut-outs, of Mao’s standard portrait in different “materials”—in brick, on a table tennis table, on a canvass splashed in red (lipstick), in corn, soy sauce or feathers—all of which are hung and arranged next to each other in the same space. Each of the portraits of Mao is only visible as a negative. Wu Hung calls the work an “anti-monument” (Wu 2005:204), negating “the very notion of the monument as an embodiment of history and memory.” Mao is present by repeated absences. What this art work does, thereby, again, is to call into question the power of the ubiquitous object itself which turns out to be but an empty shell—perhaps not even quite unlike Mao (who did not even write his own words...) during his own time?

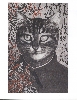

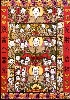

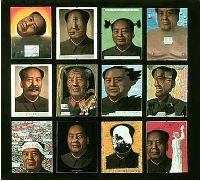

The question of meaning and the questionable pastness (or emptiness and thus, insignificance) of Mao’s presence returns for a good decade in Zhang’s works. His 1989 depiction of twelve Chairmen Mao, arranged in three rows of four (ill. 5.43), makes the viewer see a number of defaced, denatured, childlike and comic Maos, Mao upside down, Mao out of focus or fading, Mao distorted, with his nose and eyes exchanged or the two parts of his face swapped; Mao disembodied, just his head rolling around—glowing like the sun, though; Mao like a toddler with the traditional short braids; Mao naked, with his fatty breasts hanging; Mao with a tiger mask, and Mao with a Stalin-beard. The series also includes Mao lecherously ogling the Goddess of Democracy (with “women” in the speech bubble), and Mao with a headband “Serve the People” before a background of banner-waving student demonstrators in Tian’anmen Square, 1989. Mao appears as always the same old Mao, and thus, in repetition, the image is a reminiscence of the staged (not just Cultural Revolution) processions well familiar to the audiences looking at this picture.

He is presented in many different forms and from many different perspectives, however: some of the images choose standard formats, are framed and centred, others make the portrait appear skewed or even cut off parts. The artwork may be considered blasphemous and satiric, but it does not speak an unambiguously critical language. The surreal qualities of the work present the Mao one may perhaps encounter in dreams and nightmares, and one such dream would be of him during the demonstrations on Tian’anmen in 1989.

The connection with the Tian’anmen demonstrators made in the final set of four portraits is perhaps most difficult to read: Is Mao seen as a hypocrite or as a real supporter of their ideas? What does it mean that he apparently fancies the Goddess of Democracy (is his ogling and his thought “women” reduced to sexual innuendo or does he like her philosophy, too)? Does he support the demonstrators (who so look like Red Guards, whom he openly supported by wearing their arm band) when he is shown as “one of them” with his headband? Is he part of an alternative dream for Tian’anmen, or is he made responsible for the nightmare it became for many?

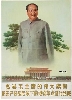

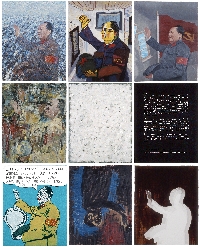

Another conceptual piece by Zhang Hongtu, his Unity and Discord of 1998, which combines many of the methods used by Chinese artists to deal with repetitions of Mao as described above, may provide further clues (ill. 5.44). When read against the countertext of Cultural Revolution MaoArt, this must appear as a piece of subversion and criticism. Mao is here repeated 9 times, in different versions of one standard pose, with the Red Guard bandage around his arm, waving benevolently to the crowds. Yet this Mao-pattern is repainted in a number of different styles from modernist art (all of which citicized during the Cultural Revolution), so, for example Cubism, Expressionism and Pop Art. His portrait is turned upside down, it is changed into a comic strip image, it is shown as a silhouette or it is completely whitened out. Perhaps most viciously, the image is substituted in one frame by the dictionary entry for the character "Mao" ? in a Chinese-English dictionary which can be read in various rather subversive ways: Mao means "mildew," Mao means "semi-finished," Mao is the name for a very small denomination of Chinese paper money, Mao is to "depreciate in value," and "to lose one's temper."

Is Mao really all of that? What is the effect of such alternative readings? Do these meanings have anything to do with Mao, the man? What is the implied audience of a piece such as this to think? Is this blasphemy? It probably is. But at the same time, it is also testimony to the continued influence and importance of repetitions and reproductions of Mao in contemporary China.