ill. 5.76, metadata

ill. 5.76, metadata

ill. 5.77, metadata

ill. 5.77, metadata

ill. 5.78, metadata

ill. 5.78, metadata

ill. 5.79 a, metadata

ill. 5.79 a, metadata

ill. 5.79 b, metadata

ill. 5.79 b, metadata

ill. 5.79 c, metadata

ill. 5.79 c, metadata

ill. 5.79 d, metadata

ill. 5.79 d, metadata

Mao as Popular God

The popular counterpart to artworks in which Mao appears as god is the Mao talisman, used as a rearview mirror ornament by taxi or bus drivers to protect both vehicle and passengers from road accidents. For quite a long while, between the early 1990s and the early 2000s, it could be seen in almost all Chinese taxis and many buses (ill. 5.76). Many of these amulets were covered in temple-like frames of gold-colored plastic and had the typical red tassels and auspicious characters dangling from them (e.g., Barmé 1996, 79). Again, the adulation of Mao makes use of and translates ritual practices from folk culture and religion (Landsberger 2002, 162). This talisman, which can hardly be read ironically, is a rather straightforward piece of evidence for a strong religious strain—one among many—within this new chapter of Mao repetitions in modern Chinese history.

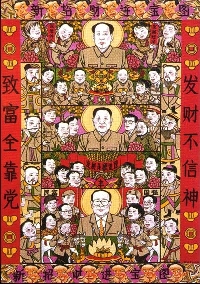

Since the early 1990s, Mao has been making a re-appearance in New Year Prints, often as the god of money (ill. 5.77). Many private entrepreneurs, representatives of the very economic model abhorred by Mao, have hung his picture behind their shop counters to bring good luck to their business. Even gamblers pray to him, hoping for good numbers (Landsberger 2002, 163). Mao wards off evil not just in New Year Prints but in anti-SARS propaganda, too.

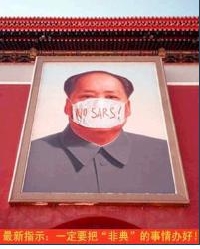

One image from the SARS crisis in 2003 shows Mao’s standard portrait on Tian’anmen wearing a mask that reads “SARS.” The caption reads: “(Mao’s) latest instruction: You must handle the SARS affair well” (最新指示: 一定要把非典的事情办好) (ill. 5.78). Mao not only does not sleep in constantly giving out his instructions, but he comes alive again when his people need him; his words and portrait were used to build up morale during the 2008 earthquake, and he has been turned into a protective symbol against all kinds of other difficulties, social upheavals, and dislocations that have constantly marked the reform period. These images can be read as evidence for a popular longing for the orderly society and the imaginary golden past as seen in the propaganda posters of the 1950s through the 1970s (Landsberger 2002, 162–63, see also DACHS 2009 Mao Memory).

Quite evidently, the religious fervor for Mao Zedong once prescribed during the Cultural Revolution remains an important element in the popularity of the Great Helmsman, Great Leader, and Great Chairman, the “red, red sun in our hearts” even today: A China Youth Daily (中国青年报) poll of 1995 found that of 100,000 respondents, 60 percent of which had been born after 1970, 94.2 percent named Mao as the most admired Chinese personality (with Sun Yatsen second). It is for this reason that millions would form the audience for the Red Sun songs, that many of them would take part and watch Red Sun quizzes and that they would be quite willing to eat their daily lunches in restaurants and celebrate their weddings in decorations with MaoArt, too (ill. 5.79a&b).

In 1992, Jia Lusheng and Su Ya published a book entitled The Sun That Never Sets (不落的太阳 Buluo de taiyang). In it, they suggest that China’s continued fascination with Mao reflects a longing for those early years when the country seemed more stable and had a “leader of mythic proportions” to revere. In view of the “Red Sun Fever” in music and the trendy commercial chic feel the revolution would acquire a few years later (with the Lei Feng sneaker by Li Ning and Linux 2000, and, more recently, Cultural Revolution-style restaurants or weddings, see ill. 5.79), it was prophetic of them to argue in 1992, that the symbols of the Chinese Communist Revolution—indeed, its whole legacy—was able to evoke primal feelings for many Chinese of pride, respect, and awe. Looking back to a golden age of the mythical Yellow Emperor and other model rulers such as Yao and Shun had been common practice in traditional China. Communist China, however, had long since preached an evolutionary model of history. Yet it has now developed the fantasy of another golden age in the past: Maoist rule (including the periods of political campaigns and purges that reached their apogee in the late 1950s and 1960s). This explains why Mao is “easily the best-selling author in Chinese history” (Leese 2006, 122) and has continued to thrive as such (with the financial crisis, this has even increased). Mao’s success is based on, but it also exists in spite of, the ritual repetition it underwent especially, if not exclusively, during the Cultural Revolution. Ritual repetition and medial multiplication made his face as well as his words into (not always disliked) propagemes.