Latent Love

A denial of sexuality is the rule in comics published during the second half of the Cultural Revolution. Accordingly, love stories that were once included in the plots are excluded or completely subdued; scenes in which sexuality, nudity, or even love or sentimentalism might play a role are eradicated. According to a summary of the “Forum on the Work in Literature and Art in the Armed Forces with which Comrade Lin Biao Entrusted Comrade Jiang Qing” (林彪同志委托江青同志召集部队文艺工作座谈纪要), sentimentalism, and especially romantic love between men and women, was taken to be bourgeois (Hongqi 1967.9:19–20).

The white-haired girl in the 1971 comic (as well as in the earlier model ballet), is no longer raped by her landlord’s son, and her romantic relationship with her fiancé Dachun is subdued, although always latent, in spite of continual erasure in successive revisions of the plot before and during the Cultural Revolution (Meng 1993): when they beam together in happiness, in the final and concluding picture, they still exude the togetherness worthy of a couple just married (see ill. 6.8). This ending is an example of what Wang Ban (1957–), who experienced the Cultural Revolution as a sent-down youth in the countryside, describes as follows: "Despite its puritanical surface, Communist culture is sexually charged in its own way. High-handed as it is, Communist culture does not—it cannot, in fact—erase sexuality out of existence. Rather, it meets sexuality halfway, caters to it, and assimilates it into its structure." (Wang 1997, 134)

Others echo his observations: “If you talk about love, then you don’t love Mao; that was the idea. But it is impossible to tell a people not to talk about love, so everybody will do so in secret.” (Playwright, 1956–). While underground art and literature reversed official restrictions quite openly, even official art did not completely eradicate love either, and love most certainly played a role in the perception of these works as well. Sexual desire remains present as a continuous and unmistakable undercurrent in these comic stories.

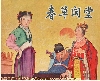

Subdued, covert, but still omnipresent appears the relationship between Fang Ming, the doctoral student at the village hospital, and Chunmiao, the barefoot doctor, in the 1976 comic Spring Sprouts. When Fang Ming and Chunmiao are shown together on a boating trip or working side by side with great eagerness and interest, their (class-based) love is only latently evident since it is only love for the Party, not for a potential sexual partner, that counts during the Cultural Revolution (ill. 6.30).

Visually, depictions of them on a boat can be considered residual influences from representations of romantic outings by shown in films made in Shanghai in the 1930s and 1940s. This is especially so when the second of the images shows Chunmiao in full view, holding the paddle, as depicted from the (loving and adoring) perspective of Fang Ming himself. The romantic mood suggested in these images finds a sharp counterpoint in the text accompanying them: it speaks a very different language.

The boating trip is in fact not a leisurely outing at all, and in seeing Chunmiao at the paddle Fang Ming is not occupied by thoughts of admiration and love. Instead, the two of them, together with a young village boy, Tugen 土根 (the name translates significantly as “with his roots in the earth”) are off to see a sick patient, and the conversation centers around grim realities: Fang Ming is quite astonished about the difficulties of reaching patients in the countryside. Yet, so Chunmiao and Tugen tell him, the situation has improved enormously since “Liberation” when villagers could never even dream of seeing a doctor in their lifetime.

Later, Chunmiao and Fang Ming are again shown at work together. Speaking from the pictorial evidence alone, their hands almost touching, their faces all smiles as they beam toward each other, one might conjecture that these two young people are in love. Yet, again, the text counters such assumptions: it is late at night, and Chunmiao is still studying while Fang Ming teaches her, so it reads (ill. 6.31).

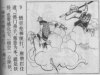

But love as prescribed in these comics is always love not for one individual but for a collective cause; it is not feelings of a singular or private self but collectively shared thoughts that may then take on a sacred value and produce uplifting effects—not quite unlike sexual love, after all (Wang 1997, 113). Love is the love of and for the Party as epitomized in many a revolutionary song sounding something like this: “Father is dear; Mother is dear, but they are not as loving as Chairman Mao. The rivers are deep and the seas are deep. Yet they are not as deep as class friendship.” Within this frame, then, sexuality and even nudity were clearly not acceptable. And, accordingly, the pig’s nipples in Zhao Hongben’s comic had to be removed for it to stay (or come back) during the Cultural Revolution (ill. 6.14-6.15).