Illustration:

ill. 5.84

Date:

early 1990s

Genre:

sculpture

Material:

scan, paper, colour; original source: sculpture

Source:

Landsberger 2002: Landsberger, Stefan. “The Deification of Mao: Religious Imagery and Practices during the Cultural Revolution and Beyond.” In China’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Master Narratives and Post-Mao Counternarratives, edited by Woei Lien Chong. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002:162, Heidelberg catalogue entry

Keywords:

Mao Zedong, God, Mao Cult, hero, worship, Mao´s portrait, leaders, popular culture, folk culture, Chinese Communist Party, idol, Mao portrait, religious, red sun, mountains, clouds, kitsch

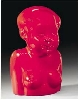

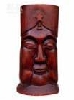

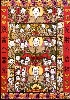

Worshipping Mao as God

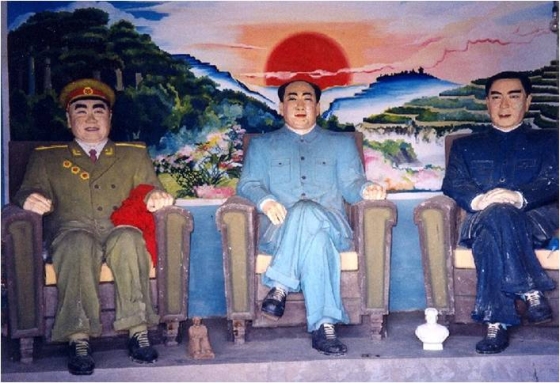

Looking at Mao images from the Cultural Revolution, as well as before and after, one realizes that while the Little Red Book, which stands for the icon of Mao, appears and disappears, the image of Mao, the man, lives on, not just on matchboxes, posters, talismans, T-shirts, greeting cards, New Year’s calendars. The hackneyed phrase that “Chairman Mao will forever live in our hearts” (毛主席永远活在我们心中) remains significant: by the early 1990s, Mao had, once more, carved out “a niche in the traditional Chinese pantheon alongside such martial heroes as Guan Gong, Zhuge Liang, and Liu Bei,” and this time, the interest in him sprung up voluntarily, from among the people (Barmé 1996, 19). He is worshipped in Buddhist temples next to other Buddhist deities (and in the company of Zhou Enlai and Zhu De as this image shows).

In Leiyang county, Hunan province, in the early 1990s, local peasants collected more than 21 million yuan (renminbi) in private funds to build the Three Sources Temple (三元寺). A huge edifice in traditional Buddhist style, the temple was dedicated to the revolutionary trinity of the Chinese Communist Party: Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and Zhu De. The largest of the three idol halls contained a six-meter-tall statue of Mao. At the height of its popularity, in late 1994, the temple attracted some 40,000 to 50,000 worshippers daily, most of them elderly, coming from many parts of the country, who used the traditional methods of burning incense to offer their worship. The complex was closed by official orders in 1995, on the grounds that it encouraged superstition, but it seemed to be functioning again by 1997 (Landsberger 2002, 161–62). (See also DACHS Continuous Revolution).

All of this makes it questionable that, as Barmé suggests, “the religiosity and fervor that characterized the earlier Cult were noteworthy for their absence” in the later Cult (Barmé 1996, 13). Indeed, if the later Mao Cult came “at the end of a decade of fads that represented the voracious consumption and rejection of both nativist and foreign cultural ‘quick fixes’ to the dilemma which China faced as a nation that had lost both its value system and its sense of purpose,” it came—among many other things—as a new system of relief and belief, too (Barmé 1996,49).