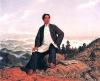

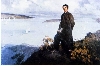

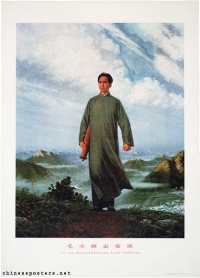

Mao goes to Anyuan

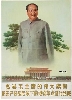

This image was declared to be a “model image” (样板画 yangbanhua). It is titled Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan and shows a stately Mao in scholar’s gown on his way to the mining town of Anyuan in eastern Hunan to support workers on strike there. Painted in 1967, it is, arguably, one of the most visible images during the Cultural Revolution and was soon called a “divine image” (宝像) (Andrews 1994, 342). Liu remembers his own reverence while creating the work and compares it to that felt by painters of religious art in Europe (Zheng 2008, 127).

Clearly, although the picture is supposed to document Mao’s historical first visit to Anyuan, the genre of history painting is here severed “from its mundane ties to an identifiable physical setting,” and thus, as Julia Andrews puts it, “it doesn’t matter where Mao is or what he is doing, for the transcendent nobility of his cause and character are clear” (1994, 339). The historical background to this picture is the hugely successful 1922 Anyuan miners’ strike in Jiangxi, during which some 13,000 miners and 1,000 railway workers walked off their jobs together. After a five-day peaceful strike, with no loss of life, no injuries, and no serious property damage, negotiations brought higher wages, better working conditions, and a guarantee of security and financial backing for the newly founded labor union and workers’ consumer cooperative, which the mining company had formerly threatened to close. The event is one of the most important legends in Chinese revolutionary history.

Of the three political figures active at the time—Li Lisan 李立三 (1899–1967), Liu Shaoqi 刘少奇 (1898–1969), and Mao Zedong—Mao was, undoubtedly, the least directly involved in the matter. Li Lisan opened a school for workers and their children in Anyuan (purportedly at Mao’s suggestion), and this ignited a flame leading to the formation of the labor union and the organization of the strike. Liu Shaoqi was sent (apparently by Mao) to Anyuan when the school was forced to close to prevent mass violence, and he personally took part in the strikes there. Mao himself merely served, quite literally, as the “remote control” of the events (Wang and Yan 2000, 56–57; Perry 2008, 1150–53). Nevertheless, Mao becomes the unquestioned hero of the story in this famous painting.

The image came into being as a group of Red Guards in Beijing arranged an exhibition in the fall of 1967 under the title The Brilliance of Mao Zedong Thought Illuminates the Anyuan Workers’ Movement (毛泽东思想的光辉照亮了安源工人运动展览会) (Zheng 2008, 119). A large group of artists was dispatched to the mine in Anyuan to “dig deep into life” (深入生活) and to talk with veteran miners about their past revolutionary activities (ibid., 122). Liu Chunhua then created his large painting, 2.2 meters in length and 1.8 meters in width, which made him a celebrity overnight. The painting was inspired, as the artist relates, in perfect Maoist lore, by a folksong: “In the year 1921, the clouds suddenly cleared and we saw the blue sky: A man of ability named Mao Runzhi traveled from Hunan and came to Anyuan” (直到一九二一年, 忽然雾散见晴天. 有个能人毛润之打从湘南来安源) (Wang & Yan 2000, 59; Zheng 2008, 123; Andrews 2010, 43).

This painting, arguably the most famous of Cultural Revolution paintings, moved the emphasis away from the event itself to its origins. It was the message of this painting that Mao’s going to Anyuan was the source of all the good fortune that was to come: he had visited Anyuan in the fall of 1921 and had discovered among the people enthusiasm about free education. He had consequently sent Li Lisan to build a school and teach there, and had thus initiated the creation of a base for the labor union and the workers’ cooperative, which later became the impetus for the strike. It was Mao’s wise strategy, then, his ideas, that had brought victory to the workers at Anyuan, so the painting insinuates.

Mao appears on a mountain ridge that could be anywhere in China. The artificially arranged clouds “allow nature to echo Mao’s movements,” as Julia Andrews (1994, 339) describes it, or, as the painter himself states, to express “the winds of revolution” (Zheng 2008, 123). By repeating a decontextualized and somehow transcendent stereotype rather than a figure historicized and localized, fixed in time and space, Mao’s appeal and his claim to greatness is universalized, and he becomes the true hyperbolic and superhuman image familiar from that famous Cultural Revolution song “Red Is the East.”

The painting would be officially declared a model painting by 1968, when it was inserted as a full-color poster and circulated with copies of some of the most important Party publications, such as People’s Daily and the military newspaper Liberation Army Daily (Yan 2008, 92), on July 1 to mark the anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party. Further reprints of the image appeared on the pages of Party publications such as the Party theory magazine Red Flag on July 1 and, a few days later, the daily Dazhong Ribao as well (ill. 5.13; DZRB 1968).