Syncretic Styles in Mao goes to Anyuan, part 3

Cultural Revolution art, and with it officially acknowledged MaoArt, too, is a mixed bag of many different styles and each of the images themselves can be considered a peculiar and particular combination of only apparently missing stylistic links (caused by a xenophobic as well as idiophobic ideology prevalent throughout parts of the Cultural Revolution) as it juxtaposed, quite paradoxically, elements appropriated from both foreign and Chinese artistic heritage and style. So, on the one hand, the plasters at the Central Academy of Fine Arts which included such works as Michelangelo’s David, or the Venus de Milo were destroyed in late August 1966 (Andrews 1994:321/322). Yet, on the other hand, Liu Chunhua who would take Raffael’s Sixtinian Madonna as the major inspiration in his Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan–and there is indeed something of Raffael’s Sixtinian Madonna in the movement of the feet and drapery of the gown–would have created a “model painting.”

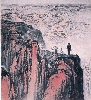

The background scenery and especially the structured mountains in Liu’s work obviously are akin to Chinese landscape painting (ill. 5.16) rather than referring to European models. This Chinese element becomes all the more striking when comparing Liu’s painting with a slightly earlier composition by Jin Shangyi (ill. 5.17) which, as Julia Andrews suggests, could well have stood model for Liu (Andrews 1994:340/341) and which recurs in many propaganda photographs (e.g.ill. 5.50).

Structurally, the two works are very similar in design: they both present Mao as an overpowering figure on top of a mountain with clouds and mountain peaks in the background echoing Mao’s movements. Yet, in the case of Jin, who depicts the older Mao in a Mao suit, the European model is much more obvious, his mountains are much less rugged, cone-shaped and sharp, they are much more flat, rolling and smooth and thus far less akin to the Chinese tradition of painting mountain ranges (ill. 5.18).

By adding iconographic elements from Chinese landscape painting into an oil composition in the style of Revolutionary Realism and Revolutionary Romanticism, Liu, on the other hand, had created a perfect piece of national flavour, combining the best of European art (no matter from what period, any European art would be considered “contemporary” or “modern” in China, see Mittler 1997) with the best of China’s traditions—just as Mao had demanded in his Yan’an Talks.