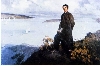

With you in charge, I am at Ease

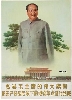

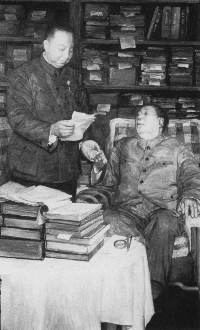

Han Xin 韩昕 (1955-) and Wei Jingshan’s 魏景山 (1943-) 1978 painting With You in Charge, I Am at Ease 你办事, 我放心 is a realist depiction of Mao shortly before his death, painted after the last published photograph. Smiling gleefully, Hua Guofeng is seen standing, to the right of Mao, towering over him (and thus somehow leaving him in the shadow, in spite of Mao’s wearing the brighter suit of the two) and holding—or rather, supporting—his limpless hand. Hua’s depiction is a sharp contrast with that of “helpless Mao Zedong” who seems to foolishly want to look at the piece of paper he himself has written for Hua stating “With you in charge, I am at ease” (Andrews 1994:382). Quite obviously, none of the Cultural Revolution directives of “red, bright and shining” are adhered to here, although they continue to reign dominant in Mao portraits of the time. This is clear when one compares Han Xin and Wei Jingshan’s image to a slightly earlier, 1977, version of the same theme by Peng Bin 彭彬 (1927-) and Jin Shangyi 靳尚谊 (1938-) which became the blueprint for huge propaganda posters to be seen throughout China since 1977 (China 2008:58 has a photograph of the poster on Shanghai’s bund).

Here, Mao and Hua are both seated, which makes their positions more equal than in Han Xin and Wei Jingshan’s depiction, where Hua is clearly foregrounded. In the 1977 depiction, Mao’s prominence is further emphasized by use of a brighter suit and his enormously large hand, the central focus of the image, is placed firmly on top of Hua’s, as he is the one who thus draws on Mao’s strength and not vice versa. There is a ray of light emanating from Mao which illuminates Hua’s face, the papers in his hand and the table next to him which is drawn with an interesting shadow effect (half of the table is in the shadow) to stress the “sun-effect” associated with Mao, not least since Cultural Revolution lore.

As in the other portrayal, the Chairman is seen here putting Hua “in charge,” entrusting him with his own duties, yet here, he is the one who reigns supreme. Quite in contrast, Mao is not a stately and dominating figure in Han Xin and Wei Jingshan’s depiction. He certainly does not have a smooth but rather an emaciated, deathly face—he is anything but a radiant source of light. Although commissioned and approved in draft for a Shanghai municipal exhibition, the painting would eventually not be considered “correct art” even in 1978. Although the two painters obviously felt that, with the end of the Cultural Revolution, a new age of realism had arrived, and had thus created this as a slightly frivolous version, perhaps, of a revolutionary realist painting, and although the painting was in fact installed in the exhibition according to plan, it was removed the night before the opening by the local administration. For Mao’s portrait, the visual norm remained, even after the Cultural Revolution, one not of realism but of “total realism,” of “factionality,” and thus, of romantic idealization (Andrews 1994:382). It is important to see, however, that in spite of the fact that, at the time, the painting did not go through with the censors, the artists’ conviction that it might, shows that the implied audience of MaoArt after the end of the Cultural Revolution is no longer as clearcut as it once was.