Beheading Mao and Putting Him to Sleep

While on the surface, these artists’ ritual repetitions of Mao look similar to those by foreign artists such as Andy Warhol. For Warhol, processing Mao (as well as Marilyn Monroe) by repetition in fact meant emptying the image of emotive content. According to Warhol, “All painting is fact, and that is enough. ... The paintings are charged with their very presence.” It was precisely to emphasize his detachment from any emotive content in these images, and very much in the spirit of Benjamin, who would have stated exactly this about the effects of mechanical reproduction, that Warhol silkscreened them on to canvas in batches, implying that they could be repeated ad infinitum (Read 1985, 298).

The Chinese artists’ approach, on the other hand, is different: for them, creating repetitions of Mao, deconstructing and rationalizing Mao, the myth, was an attempt to deal with the formidable formative powers of his image that they themselves continued to feel so acutely. It was, therefore, precisely to create works with emotive content. Their attempt to transform Mao from god to human being was an attempt to create an image with whom they could carry on living more easily—for live with it they must continue to do.

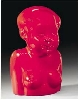

Sui Jianguo 隋建国 (1956–) a Beijing sculptor, after repeatedly “beheading” Mao in his Legacy Mantel (衣钵) series of Mao suits modeled in all sizes, all colors, and all materials but without a head (the first of which were produced in 1997), went on, finally to “putting Mao to sleep” in a sculpture entitled Chairman Mao Sleeping (睡觉的毛主席) in 2003. He describes this experience as follows: “I realized Mao is not a God because God doesn’t sleep. Now I should stop thinking about Mao and take care of my own life.”